- Magazine Article

- Exhibitions

African Master Carvers

Nine sculptors of traditional African artworks rise from anonymity

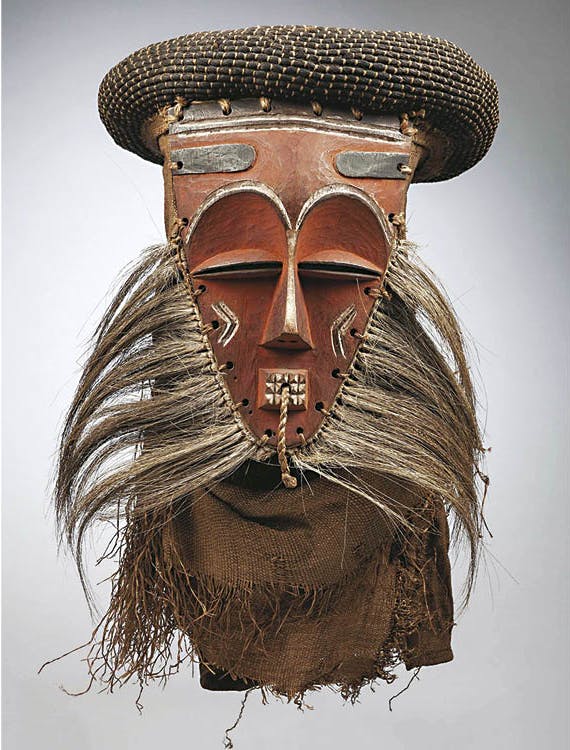

Forehead mask (Munyangi or Kindjinga), before 1958. Carved by the (Eastern) Pende artist Kiyova (dates unknown). Democratic Republic of the Congo, West Kasai region, Luaya-Ndambo village. Wood, pigment, fabric, fiber, ram’s hair; h. 20 cm. Private collection. Photo: © Christie’s

Traditional African arts in collections and museum exhibitions in Europe and the United States are generally ascribed to an unknown or unidentified artist or, more commonly, to a culture or people. Typically, few if any artists’ names are associated with an object. In fact, merely a handful of the Cleveland Museum of Art’s more than 300 African holdings can be associated with some certainty to named individuals. Of course this does not mean that the people who used the works did not know their makers’ identity. The alleged anonymity of these artists is largely the result of the limited interest on the part of mostly non-African collectors. This has much to do with the fact that when the works were first acquired and exhibited, they were not considered to be art but instead seen as exotic curiosities or, at best, crafts. As an antidote to the numbers of unidentified artists presented in the majority of African art publications and exhibitions, African Master Carvers: Known and Famous celebrates the careers and oeuvres of nine sculptors who were locally recognized and even praised during their lifetime.

A few early scholars of African art devoted some interest to the life and work of the artists they met during field research in the 1930s, but sustained interest in the subject did not start until the 1950s and ’60s. Unfortunately, by then, detailed information on many artists of the past had been irretrievably lost. However, in the absence of signed works, scholars of African art have adopted a method common in the study of ancient Greek, medieval, and early Renaissance art, which consists of identifying an artist’s hand by analyzing stylistic features. Through meticulous description and comparison of anatomical details such as eyes, ears, and hands, they have been able to attribute specific works to individual artists to whom they assigned nicknames or so-called names of convenience, several examples of which are included in the exhibition. Most often, these nicknames refer to the location where the alleged master was believed to have been active. Lacking any geographical reference, still other hands are named after a characteristic formal or iconographical feature, such as the “Baboon Master” for Cleveland’s magnificent staff by an anonymous artist of the Tsonga or Zulu culture of Southern Africa.

African Master Carvers features four sculptures on loan from the Indianapolis Museum of Art and two privately owned masterpieces alongside nine works from the CMA collection. Works carved in wood and ivory by artists of various sub-Saharan cultures illustrate the wide-ranging individuality of the artistic legacy of the African continent. Because of the persisting Euro-American preference for three-dimensional objects in durable materials, the exhibition’s selection of objects focuses on male artists. Three of the best-known master carvers presented in the exhibition were members of the Yoruba culture in Nigeria. One of the most prominent historical Yoruba artists is a man called Bamgboye (1893–1978), who lived in the Ekiti region in northeastern Yorubaland. The Cleveland Museum of Art’s monumental helmet mask that was formerly in the collection of American horror film actor Vincent Price is generally considered to be among Bamgboye’s most virtuosic and exuberant realizations of the Epa mask genre. His contemporary Agbonbiofe (died 1945)—who carved the female figure with a bowl on loan from a private collection—was the leading exponent of the Adesina family in the same Ekiti region. He exhibited a radically different style in works that are admired for their self-contained, quiet mood.

Today, the presumed anonymity of the makers of several of the works included in the exhibition can be firmly refuted. However, while some documentation has been gathered on the biographies and methods of a number of other sub-Saharan artists, our general knowledge remains quite superficial. Unfortunately it will most likely be impossible to retrieve the names of most of the makers of the thousands of African artworks that appear in publications and collections around the world. Yet, it is important to remember an observation by renowned art historian and curator Susan Mullin Vogel in her article “Known Artists but Anonymous Works” in the journal African Arts (Spring 1999, page 40): in its original African context, authorship is seldom seen as a significant attribute of the work of art. Indeed, because these objects often become animate and empowered, for African audiences and users the person who consecrates them is usually more important than the person who creates them. Consequently, the names of other individuals, such as owners and patrons, are frequently more readily remembered than those of artists.