Ancient Artworks Echo the Origins of the Olympic Games

- Blog Post

- Collection

The Olympic cauldron will be lit during the Opening Ceremony at the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games later tonight and over the next two weeks, a worldwide audience will watch as thousands of athletes compete, realizing lifelong dreams. Although a number of their disciplines are entirely modern, many have been practiced for millennia; some even stretch back to ancient Greece, where the Olympic Games originated as a quadrennial festival held at the Sanctuary of Zeus in Olympia (opens in a new tab). There, tradition tells us, the games were first held in 776 BC, initially with only a single footrace. Covering one length of the stadion (stadium) — 600 Olympic feet, or 192 meters — this race remained the marquee matchup (in today’s terms) for centuries, with each Olympic stadion winner attaching his name permanently to “his” four-year period.

To those who associate one (or more) modern Olympic Games with the “world’s fastest man” — think of Jesse Owens (opens in a new tab), Carl Lewis (opens in a new tab), or Usain Bolt (opens in a new tab) — this may sound familiar, but in antiquity, winners were by some measures even more famous. For in a world in which each Greek city-state reckoned time in its own way, the Olympic stadion victor lists constituted the only universally recognized chronological system. Indeed, athletics aside, these lists have provided absolute dates for many historical events.

At Olympia, additional events were added to the program over time, including several still familiar today: wrestling and pentathlon (a five-sport event combining running, wrestling, javelin, discus, and long jump; 708 BC); boxing (688 BC); chariot racing (680 BC); and pankration (opens in a new tab) (“all-powerful” fighting, prohibiting only biting and gouging) and horse racing (648 BC).

Still later additions (396 BC) crowned heralds and trumpeters, who would then quiet the crowd and introduce events, competitors — only freeborn Greek-speaking men and boys (competing separately) — and results. Olympic contests divided broadly into gymnic and hippic, or nude and equestrian, the former term indicating one major difference between ancient and modern competitions! While Greek charioteers typically appear fully clothed in artworks from the period, bronze riders like this one are sometimes nearly nude.

Turning his head and well-muscled torso, he still holds the handle of his whip or goad, urging on his mount (now lost).

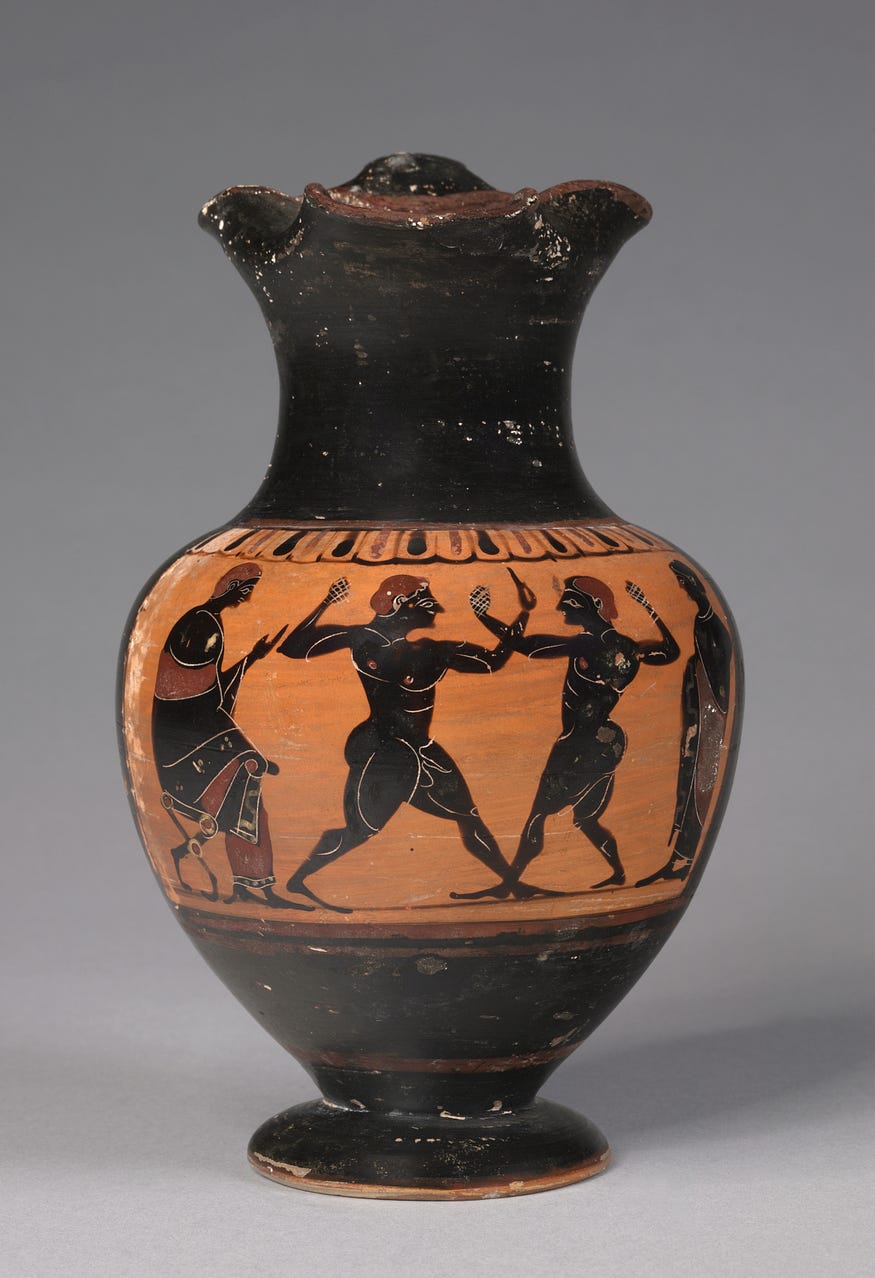

Nudity apart, other details also differentiate certain ancient events from today’s parallels. On this black-figure wine jug, two stout young boxers face off.

While one has both hands wrapped for fighting (in leather straps known as himantes), the other uses an unwrapped bare hand to fend off punches. Two figures flank them — likely a spectator and a judge, who would enforce rules but not declare the winner; this was decided simply when one fighter would not or could not continue.

Traditionally, Olympic victors received ribbons, palm branches, and crowns of freshly cut wild olive (with no second- or third-place prizes). Although officials did not award monetary prizes at Olympia, many city-states compensated their victorious athletes handsomely. Moreover, both at Olympia and back home, victors were often honored with large statues, celebrating and glorifying the strength and beauty of the male form. Now mostly lost, such large dedications may find echoes in smaller bronze statuettes like these.

The first, striding forward with right arm raised, probably represents a pentathlete preparing to throw a javelin. Combining an Archaic smile and patterned musculature with a convincingly twisted torso, he exudes power and confidence, presaging triumph.

The more slender athlete, by contrast, pauses after victory, looking down to make an offering with his lost right hand, perhaps thanking a god for good fortune. His gently turned head and contrapposto stance exemplify important sculptural developments of the Classical period.

Along with sculptures of athletes, Olympia housed many elaborate buildings and artworks dedicated to the gods. Most famous was Pheidias’ (opens in a new tab) colossal statue of Zeus, a wonder of the ancient world. Now lost, the much-admired statue may have resembled the image on this coin, where the seated god holds his scepter and — most fittingly at the birthplace of Olympic competition — a statue of Nike (opens in a new tab), the winged goddess of victory.

As you watch the modern-day Olympics in Tokyo over the following weeks, be sure to visit the Greek art galleries (102B and 102C) and the Collection Online for a closer look at ancient artworks inspired by athletic and equestrian competition.

Want to learn more? Here are suggestions for further reading:

· https://olympics.com/ioc/ancient-olympic-games/history (opens in a new tab)

· Miller, Stephen G. 2004. Ancient Greek Athletics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

· Swaddling, Judith. 2004. The Ancient Olympic Games. 3rd ed. London: The British Museum Press.