Celebrating Ceremony: Native American Drawings Now on View

- Blog Post

- Exhibitions

Did you know? Light-sensitive objects in the museum’s Sarah P. and William R. Robertson Gallery of Native American Art (gallery 231) are rotated out annually in order to increase the lifetime of the object by decreasing light exposure. New this year, in addition to baskets and textiles, are two works on paper, offering visitors the first opportunity in at least two decades to see Native American drawings from the collection.

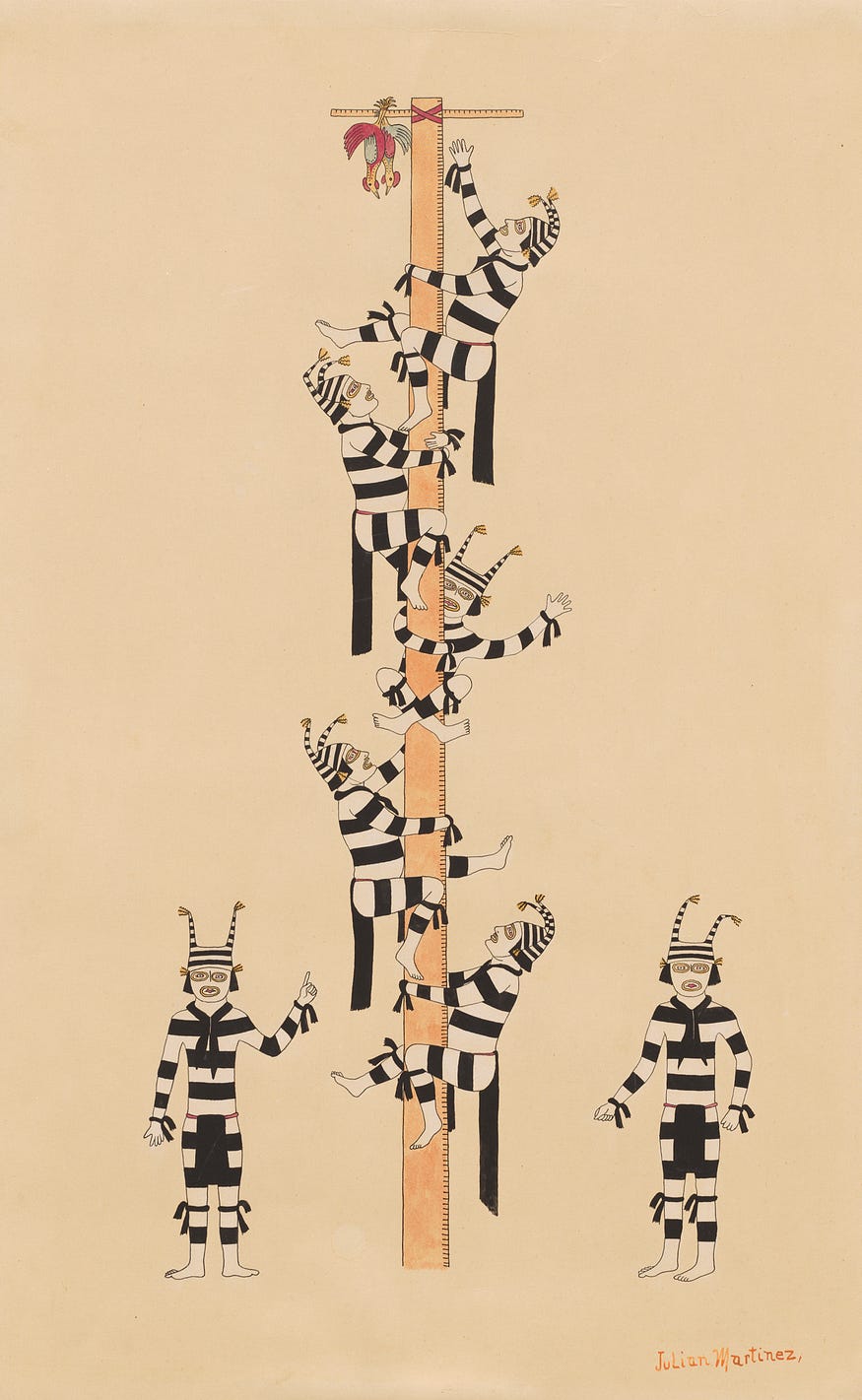

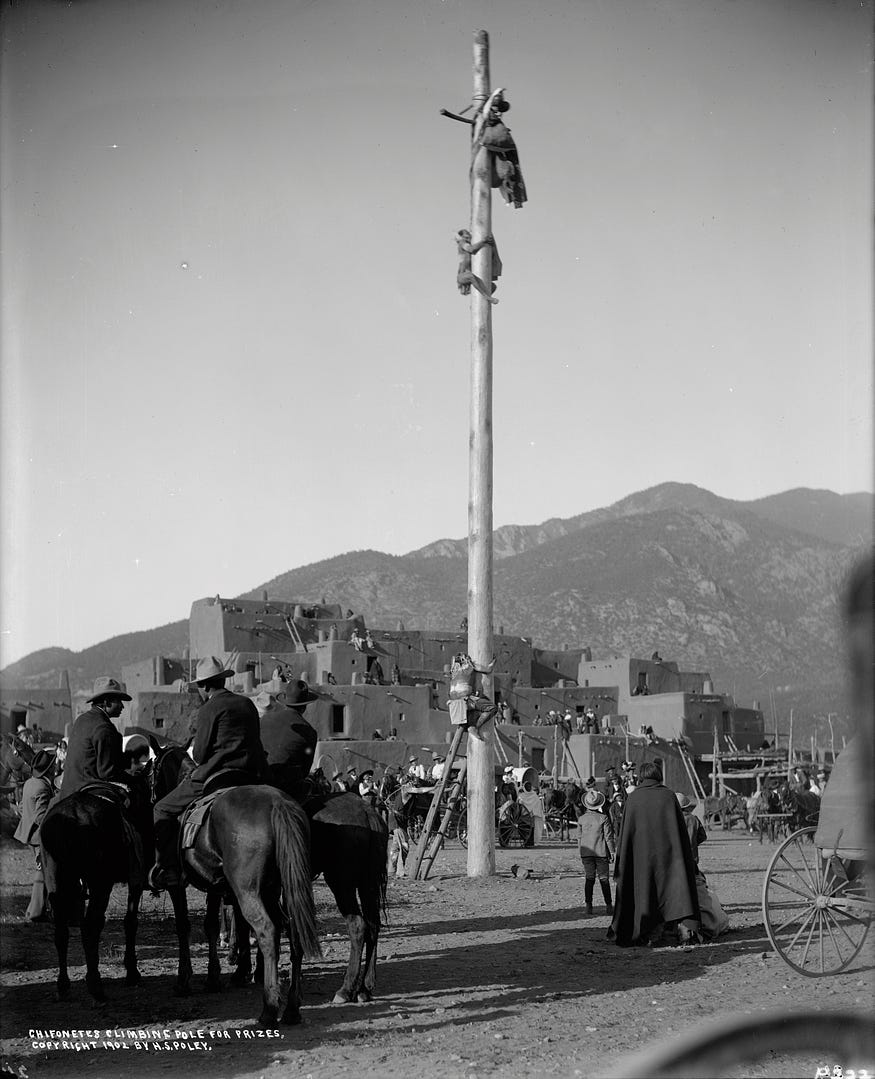

On view through August 2020, the current installation features the Koshare Contest, a drawing of a pole climb in Taos, New Mexico.

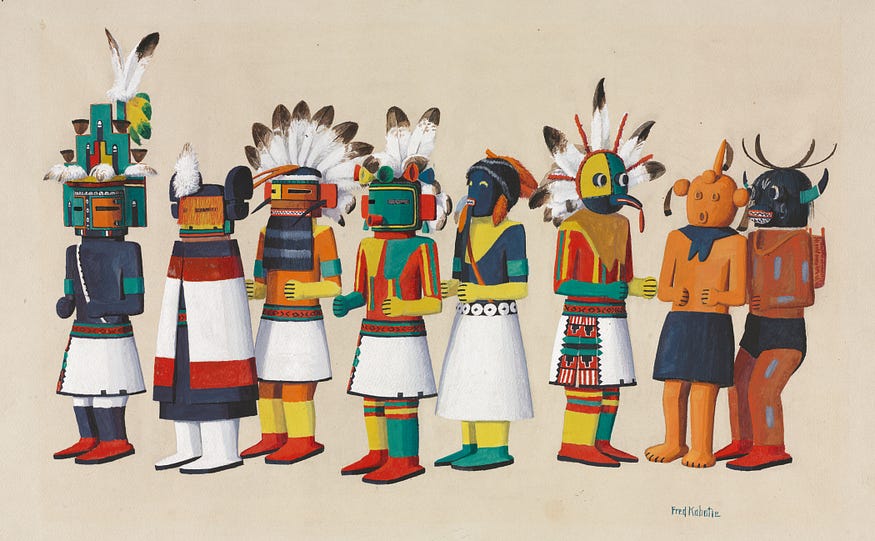

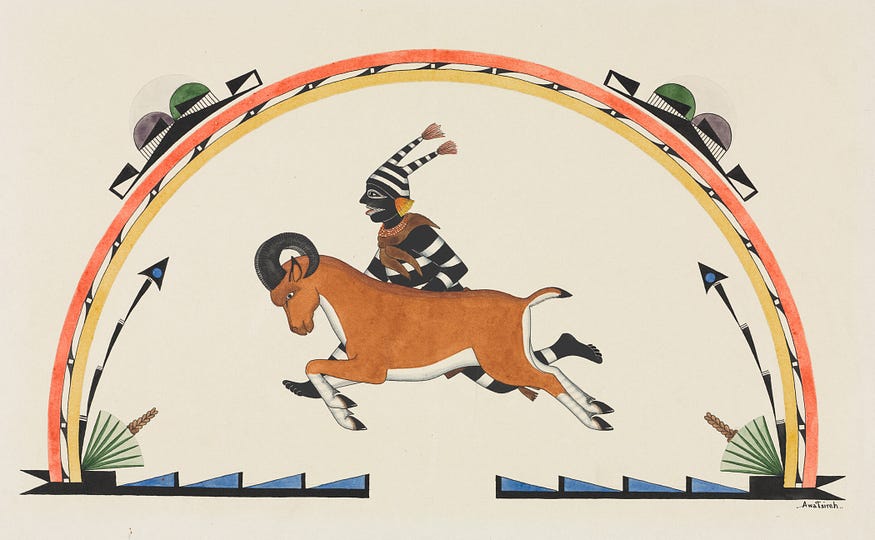

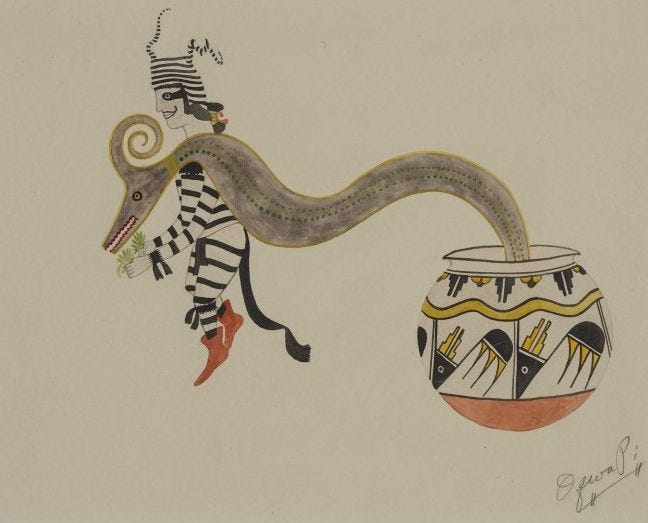

Pueblo artists have long been recognized for their skill in creating pottery and textiles. Watercolor was introduced by the Europeans and Americans; one of the first Pueblo artists to embrace it was Ta’e (Crescencio Martinez, 1879–1918) of San Ildefonso Pueblo. Although he died before his work was exhibited, he gained posthumous national recognition, and he became known for his depictions of costumed dancers at San Ildefonso. His success encouraged younger artists such as his nephew Awa Tsireh (Alfonso Roybal, c. 1895–c. 1955), Ma-Pe Wi (Velino Shije Herrera, 1902–1973), Naqavoy’ma (Fred Kabotie, c. 1900–1986), and Julian Martinez (Pocano, c. 1885–1943). Many of them began their artistic careers by painting pottery, and together they are considered the founding generation of modern Indian painting.

The initial style of modern Pueblo painting is rooted in ancient wall paintings and rock art as well as later pottery and textile designs, sand paintings, and kiva murals. This blending results in clear, crisp figures on a flat background; the figures are usually engaged in dancing, hunting, or performing genre activities.

With no visual clutter and a keen sensitivity to color, the drawings show great fluidity and confidence. In addition to figural scenes, there are complex abstract patterns and symbols similar to the designs favored on pottery.

This style would evolve, and by the late 1950s the second generation of painters focused more on individual style, while still expanding and building upon the earlier works by adopting techniques such as perspective and modeling.

September 30 is San Geronimo (Saint Jerome) Feast Day at Taos Pueblo. Patron saint of the pueblo, San Geronimo is celebrated with dances, races, and a mass in his honor.

Spanish friars who arrived in the 17th century attached the saint’s name to an indigenous festival that centers around the harvest. Attended by locals, visitors, and tourists, the festivities climax when a tall pole, at least 30 feet in length, is erected, greased, and topped with treasures such as lamb, corn, and vegetables; in the CMA’s drawing, colorful chickens are tied to the top. Then the koshare, ceremonial clowns who entertain the crowd throughout the day with irreverent antics, attempt to climb the pole.

The crowd cheers and roars with laughter as the koshare clamber up a few feet and then slide back down. Eventually one is successful; as the winner, he returns to the ground with his treasure, and the day of celebration ends.

Although pole climbing is unique to Taos Pueblo, the koshare appear at other dances at eastern and western pueblos. This includes the Corn Dance, which features a reenactment of an ancient ceremony in which the ancestral spirits consult on the upcoming dance. Scouting the points of the compass for enemies, the koshare slowly survey the plaza where the ceremonial dance is to occur.

During the dance itself they perform the dance’s symbolic gestures while moving around the other dancers who remain in formation. Another appearance by the koshare is made at the Deer Dance, celebrated on Christmas or King’s day. On this day they spend the morning running from house to house collecting food presents with much shouting, gesturing, singing, and antics.

The concept of a ceremonial clown appears in many world cultures throughout history, such as in Egypt by about 3000 BC. Among Tewa and Hopi speakers of the New Mexican pueblos, the koshare are only one of several types of male clowns. They are recognizable immediately, as their bodies are painted with wide black and white stripes, their faces are white with large, dark circles around the eyes and mouth, and they wear loincloths. Their heads are adorned with striped hats with hornlike projections sprouting corn husks; sometimes the horns are made of hair bound with the husks. Besides supplying comic relief during ceremonial performances, the koshare are said to represent the spirits of the dead; their black-and-white striped bodies denote their ghostly state. As spirits who would normally be invisible, they have a privileged status that enables them to behave freely and make fun of human foibles. They mediate between the worldly and otherworldly domains, the sacred and the profane.

Their role is of great importance; while their antics are entertaining, by challenging acceptable social norms, they are in fact dramatically demonstrating unacceptable behavior. Thus, they are keepers of societal behavioral norms, and no one is safe from their mockery and ridicule.

In origin tales and myths, the koshare are associated with the sun, cornmeal, the power of fertilization, and life-giving rain — all elements essential to survival. They most often appear at the ritual dances associated with the change in seasons. When Europeans arrived in the Southwest, they persecuted the koshare, who in response withdrew into secrecy but continued their ritual practices. Today they thrive and have become a popular subject for many Pueblo artists.

The Koshare Contest in the CMA collection is signed by Julian Martinez, who painted in watercolor but is best known for his painted pottery, which he created with his wife, Maria Martinez (c. 1887–1980). Stylistically, however, the watercolor is more like those by Awa Tsireh. The two worked closely together, often showing work in the same exhibitions, but more research is needed to better understand the relationship of their styles.

Check out this installation in person, on view through August 2020 in gallery 231.