A Field Guide to “Medieval Monsters: Terrors, Aliens, Wonders”

- Blog Post

- Exhibitions

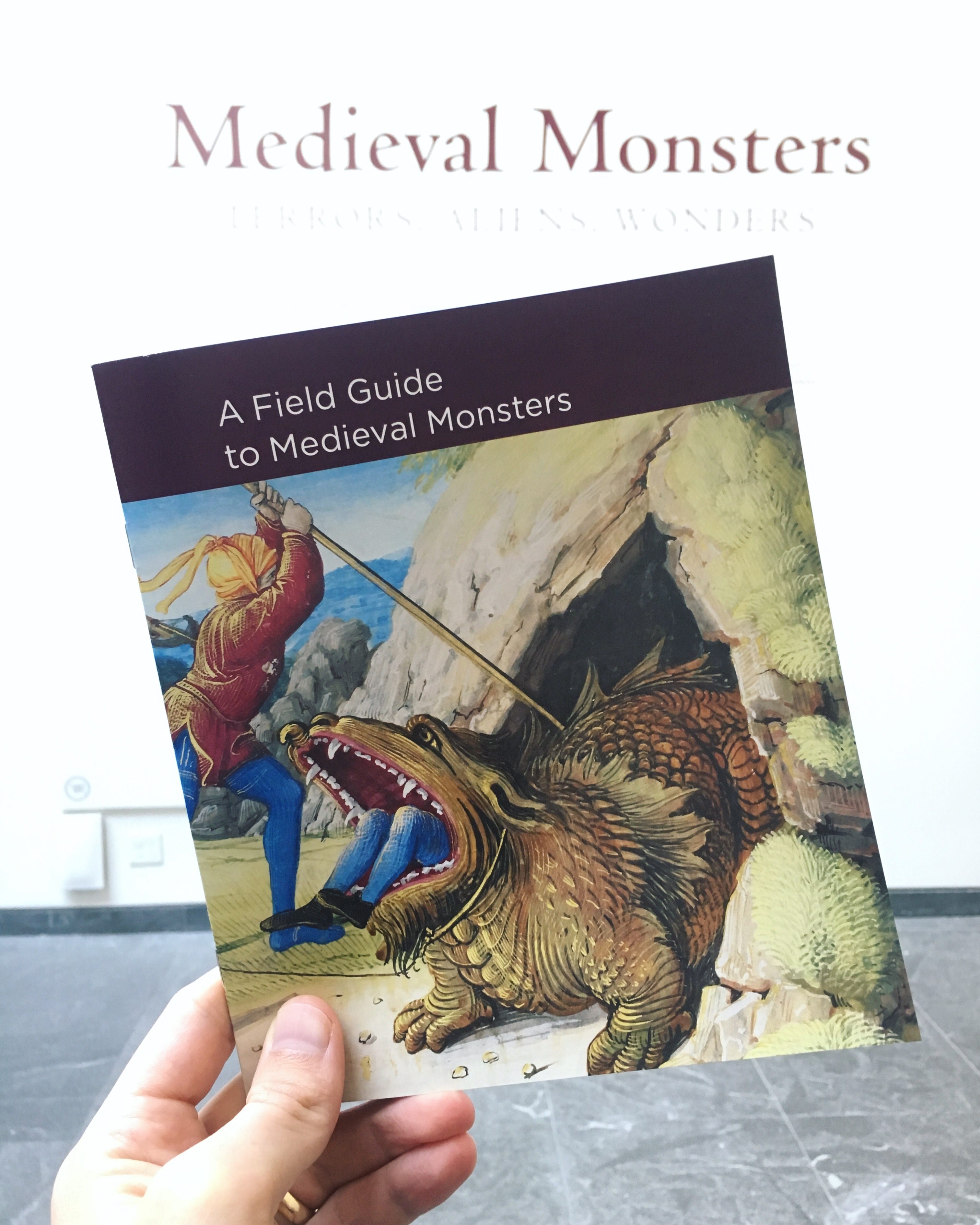

Medieval Monsters: Terrors, Aliens, Wonders, on view in the Kelvin and Eleanor Smith Foundation Exhibition Gallery through October 6, 2019, explores the function, deployment, and reception of monstrous images during the Middle Ages. In the essay below, Kress Interpretive Fellow Emily Hirsch discusses the exhibition; its interpretive gallery guide, “A Field Guide to Monsters”; and the ArtLens App tour “Beyond Medieval Monsters.” Dive deeper into the exhibition with the guide below, and check out Medieval Monsters: Terrors, Aliens, Wonders in person, on view now.

In the exhibition Medieval Monsters: Terrors, Aliens, Wonders, the term monster is applied broadly, encompassing the real and imaginary, human and beast. This includes mystical creatures that are familiar today, like dragons and unicorns, but also includes groups of people who were figured as monstrous because of their “otherness,” like women and non-Christians. Even creatures known to exist, such as elephants and leopards, were viewed as monsters because they came from so-called exotic locales and were therefore ascribed with magical properties.

The images in Medieval Monsters are drawn primarily from religious manuscripts of the Middle Ages, including sacramentaries, psalters, bibles, and books of hours, which were often highly decorated with intricate illuminations. Many of these texts come from the Morgan Library & Museum in New York City, which has one of the most distinguished collections of Western manuscripts in the world. The addition of sculptures and prints from the CMA’s collection helps visualize our understanding of monsters from the ancient through the early modern periods.

Divided into “terrors,” “aliens,” and “wonders,” each section of the exhibition explores a different facet of what monsters meant to the medieval person. In “terrors,” one can find images that were used to scare people, eliminate dissent, and promote Christian faith. Depictions of Saint George — the soldier-saint who slayed a dragon terrorizing a Libyan city in exchange for the populace converting to Christianity — demonstrate the miraculous triumph of Christianity in the face of monstrous threats.

“Aliens” presents monsters that were used to demonize social groups that did not adhere to the standards of a highly stratified society dominated by white Christian men. In this image of a siren, a bird-woman hybrid monster that originated in Greek mythology, she is surrounded by men who have drowned after being lured by her irresistible song. The imagery of the siren suggests that feminine corruption is ultimately responsible for the downfall of men.

The last section of the exhibition, “Wonders” addresses the monsters that sparked curiosity and awe for the medieval person. Fabled creatures like unicorns were associated with the Virgin Mary and their existence was thought to be proven by the discovery of narwhal tusks, a type of Arctic whale with a single protruding tooth, which resembles the unicorn’s elegant horn.

To help visitors recognize and learn more about the various monsters they may encounter, the Interpretation department worked with Amanda Mikolic, curatorial assistant, to compile a companion gallery guide. The “Field Guide to Medieval Monsters” identifies 30 monsters that can be spotted throughout the exhibition, and includes enlarged details from the manuscript pages and additional information that may not be addressed in the object’s label.

Arranged in alphabetical order, this guide begins with the Basilisk, a reptilelike creature often described as a crested snake or rooster with a snake’s tail, and ends with the Ziphius, a beaked whale thought to menace seafarers. Other highlights include the wild men, humanoid creatures covered in hair, and the Tarasque, a monster similar to a dragon that was alleged to have terrorized the countryside of southern France before it was tamed by Saint Martha.

After leaving the exhibition, visitors are encouraged to spend time in the CMA’s permanent galleries, where monsters can be found in artworks from across all time periods and cultures. The ArtLens App tour “Beyond Medieval Monsters” features six artworks depicting monsters that range from ancient to modern, like the Phoenician Decorative Plaque: Winged Sphinx (900–800 BC) and Max Beckmann’s The Last Duty of Perseus (Hercules) (1949).