The Jarrells’ Heritage: A Joyful Changing Same

- Blog Post

- Events and Programs

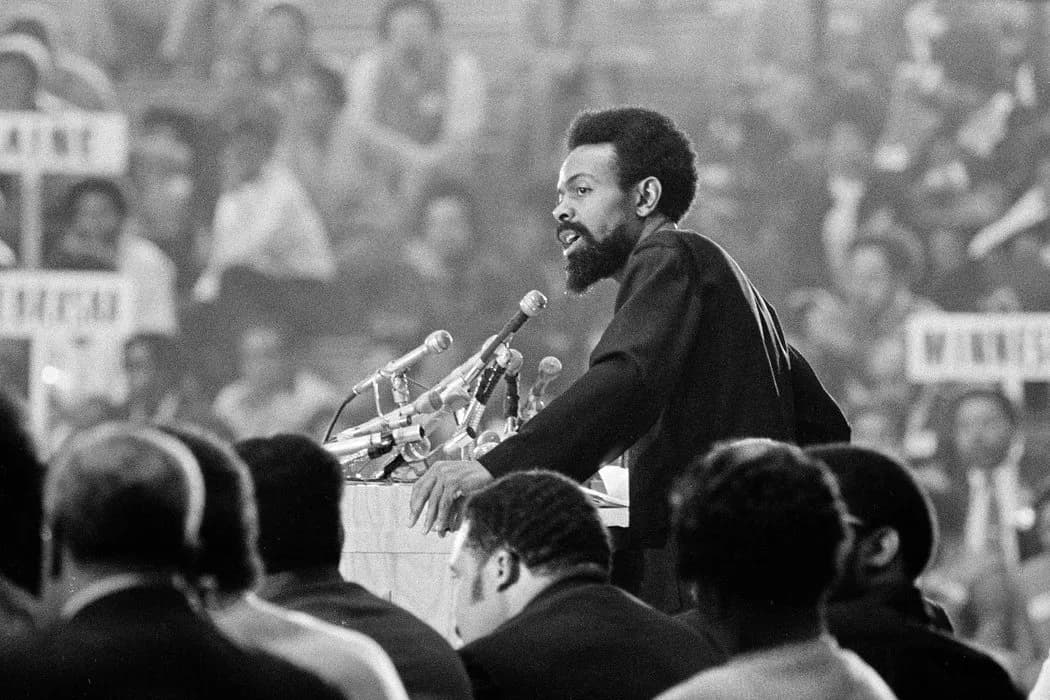

Amiri Baraka at the National Black Political Convention in 1972. Image courtesy Gary Settle/The New York Times

Acclaimed poet, playwright, and Black Arts Movement galvanizer Amiri Baraka cut to the heart of the matter when he acknowledged the evolution of black music as the “changing same.”

Under this designation, the lineage of black music genres — from the drums and koras of West Africa to the electric guitars and drum machines of rock ’n’ roll and hip-hop — composes the grand narrative of black music and black people.

It is this same unbroken, yet ever expanding, descent of life, creativity, migration, and perseverance upon which Jae and Wadsworth Jarrell bring forth beauty and vibrancy in their artwork. The current retrospective Heritage: Wadsworth and Jae Jarrell, on view at the Cleveland Museum of Art through Sunday, February 25, highlights the ways in which deterministic beauty shines through in both the African American historical narrative and in the Jarrells’ personal journey. Now in their lively eighties, the Jarrells have spent over half their lives creating portals into the optimistic side of life.

Jae’s and Wadsworth’s work first came to prominence in the 1960s and ’70s at a moment when black artists, musicians, poets, playwrights, and dancers understood the necessity of their art to directly engage their own black community.

In cities such as Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York, black artists were creating new colors and vocabulary with which to display new possibilities. But this new language wasn’t intended to separate them from the communities from which they sprang and joined, but to be in direct conversation with them. Art and music of the era mimicked the call and response pervasive in much of the music in the African diaspora.

It is now some fifty years later, at a moment when beauty feels more necessary than ever. And thankfully we have the vibrant work of the Jarrells to contemplate and respond to.

Yes. Their colorful and enlivening retrospective, Heritage, is a call that compels a response.

This is one of the most notable traits of African diasporic music: one issues a pronouncement or presence and anticipates its rejoinder. More than a musicological necessity, it is a building block of the community’s fabric. A way of saying “I am they.” An acknowledgment that there can only be a whole when we are inclusive of all. We can trace call and response from the engagement of drummers and dancers to the swapping of solos on the jazz bandstand to the interaction between rappers and deejays.

[Call and response is…] “More than a musicological necessity, it is a building block of the community’s fabric. A way of saying “I am they.” An acknowledgment that there can only be a whole when we are inclusive of all.” — Fredara Hadley

In conjunction with Heritage and in the community spirit with which the Jarrells created much of their work, the museum asked visitors to submit a song that came to mind after touring the exhibition. As varied as the people who viewed Heritage, the submissions echo the expanse of time and space captured in Jae’s and Wadsworth’s love-laden work. Together, the songs serve as the Jarrells’ living, collaborative soundtrack.

Some songs serendipitously dovetail in poignant ways. For example, one visitor responded with the freedom-minded Negro spiritual “Go Down Moses,” while another supplied Roberta Flack’s emphatic “Go Up Moses,” in which she soulfully sings the chorus: “We been down too long.” Songs such as Sister Sledge’s “We Are Family,” Ray Charles’s “I Got a Woman,” and Pete Rock and C. L. Smooth’s “T.R.O.Y. (They Reminisce over You)” shift our gaze to our most personal relationships. This is a central theme in both the life of the Jarrells and Wadsworth Jarrell’s Portrait of Jae.

Video courtesy YouTube.

Video courtesy YouTube.

Yet in the midst of abundant joy and love come resistance and questions. One visitor submitted Curtis Mayfield’s rousing anthem “Move on Up,” while another responded with Janis Joplin’s searing rendition of “Summertime.” Marvin Gaye’s contemplative “What’s Going On” is a question that repeatedly returns.

Video courtesy YouTube.

Video courtesy YouTube.

Courtesy of Motown Records.

These responses to the call and inspiration of the Jarrells spanned sixteen genres and included music from the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries. The diversity of songs speaks to both the breadth of emotion that emanates from Heritage and the Jarrells’ ability to capture that undulating, changing same that propels much of black art and music through the past and present, and into our future.

. . .

CMA hosted a Heritage: Wadsworth and Jae Jarrell listening session in which audience members could explore the link between visual art and music using a selection of submitted songs as a point of conversation and storytelling between audience members and a panel of music enthusiasts. This program was moderated by Fredara Hadley, Visiting Assistant Professor of Ethnomusicology at Oberlin Conservatory (opens in a new tab).

Panelists included:

Aseelah Shareef, Karamu House (opens in a new tab)

Gabe Pollack, BOP Stop at the Music Settlement (opens in a new tab)

Jason J. Rawls (DJ J Rawls (opens in a new tab))

Brittany Benton (DJ Red-I (opens in a new tab))

Check out the full list of songs from the listening session (opens in a new tab), and photos from the event below!

Heritage Listening Session Photo Album (opens in a new tab)