Less is More

- Magazine Article

- Collection

- Exhibitions

An exhibition of minimal art exemplifies "What you see is what you see"

Jane Glaubinger Curator of Prints

Around 1960 an avant-garde style of art emerged that focused on geometric forms depicted in solid, flat colors. This spare, objective approach stood in stark contrast to Abstract Expressionism, which had dominated the preceding two decades. Extolling the random, accidental, and intuitive, the gestural brushwork of Abstract Expressionism communicates the artist’s emotional state and the angst of postwar America. Minimal works of art, on the other hand, allude to nothing beyond their literal presence, and color is nonreferential. These concepts echo the 1910s when abstraction developed and some artists like Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian also used geometric shapes—albeit for different purposes—as a basis for their endeavors. Reducing works of art to their most essential elements continued to reflect a variety of ideas and concerns later in the century when the artists represented in Less Is More: Minimal Prints, currently on view in the prints and drawings galleries, came to maturity.

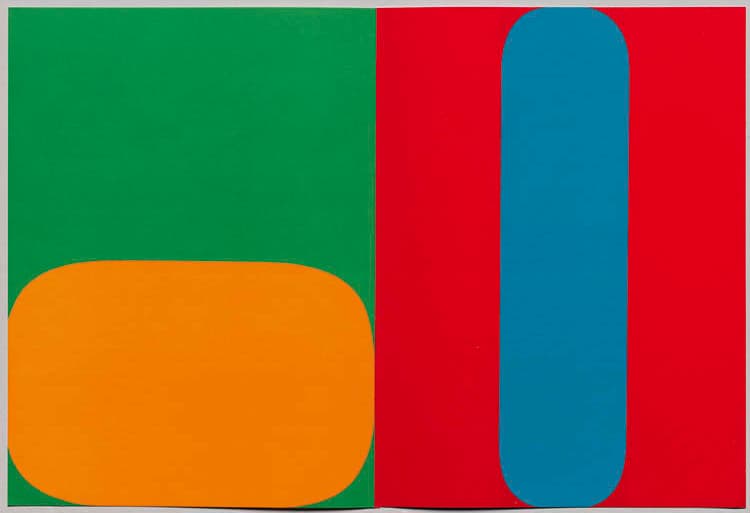

Untitled (pages 6, 11) 1964. Ellsworth Kelly (American, born 1923). Lithographs; 38.1 x 55.9 cm (both pages across sheet). Gift of Donald F. Barney Jr. and Ralph C. Burnett II in honor of Diane De Grazia 2000.39.c,e. © Ellsworth Kelly

Ellsworth Kelly was an important early proponent of a minimal style. Drafted into the U.S. Army in 1943, he served in England, France, and Germany. A few years after his discharge he returned to France in 1948 and remained there until 1954, the most important formative period in his artistic development. In 1949 Kelly made contour drawings of plants in simplified and flattened shapes that provided, he said, a “bridge to the way of seeing . . . paintings that are the basis for all my later work.” He sketched the shapes of shadows, buildings, and other forms, and these notations became like a dictionary of motifs, the source for his simplified and abstracted images.

In 1951 Kelly met Aimé and Marguerite Maeght, owners of a Paris gallery devoted to contemporary art who also ran a lithography workshop to make available to a broader audience less expensive printed imagery by artists of the time. In addition to various publishing ventures, Aimé sponsored the periodical Derrière le miroir, which included original prints and commentary on artists by writers such as Samuel Beckett, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Tennessee Williams. Kelly’s work was featured in the November 1964 issue to coincide with his second one-man show at the Galerie Maeght. Like Untitled (pages 6, 11), Kelly’s sharp-edged, unmodulated radiant forms, based in nature, may be intuitive and irregular, but they are always carefully adjusted in terms of color, size, and scale to avoid the illusion of depth.

Star of Persia I 1967. Frank Stella (American, born 1936). Lithograph; 66 x 81.3 cm. Gift of Agnes Gund in memory of Frances Hurley 1972.92. © Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Frank Stella, like Kelly, wants to expunge the illusion of three-dimensional space on a flat support. Any mark on a background begins to denote spatial depth, so he covers the entire area with a single abstract motif that destroys the impression of foreground and background. This “regulated pattern . . . forces illusionistic space out of the painting at a constant rate.” In Star of Persia I the white spaces between unmodulated colored V-shaped bands flow into the background, flattening the design. “My painting is based on the fact that only what can be seen there is there,” Stella is fond of saying. “What you see is what you see.” He maintains that his sole concern is such formal properties, but his titles are allusive; Star of Persia references a 19th-century clipper ship.

An avid printmaker, Stella was well aware that paper tends to absorb lithograph inks, weakening the image. He thus took advantage of newly available nonabsorbable metallic inks to strengthen the visual effect of Star of Persia I. Six colored inks were printed over a metallic silver base that subtly toned and raised them.

Five Threes 1976–77. Brice Marden (American, born 1938). Etching and aquatint; 53.4 x 75.9 cm. Mr. and Mrs. Richard W. Whitehill Art Purchase Endowment Fund 1996.23.1. © Brice Marden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Brice Marden’s work is also influenced by his own artistic and personal concerns. For instance, he conceived of the set of five prints titled Five Threes as studies for his three 1977 “moon” paintings. The prints’ tripartite format symbolizes the waxing, full, and waning lunar phases and also reflects Greek mythology. The Triple Goddess personified primitive woman as both creator and destroyer. As the New Moon or Spring she was girl; as the Full Moon or Summer she was woman; as the Old Moon or Winter she was hag.

Greek culture has been important to Marden since his first visit to the Mediterranean in 1971. The blue ink used in three of the Five Threes prints evokes sea and sky while the rectangles and bands recall the lintels and posts of the ancient temples the artist sees on his annual trips to Greece. The arrangement also resembles a closed door, a recollection of a trip to Egypt where massive stones block the entrances to tombs and is similar to the Roman fresco paintings he admires at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In Five Threes he pays homage to the trompe l’oeil nature of paneling and friezes, creating the illusion of shallow space yet simultaneously reinforcing the flatness of the picture plane by varying the density of the cross-hatching and aquatint.

Marden works within a restricted abstract format, choosing muted colors, but insists that his work expresses emotion. “Within these strict confines,” he says, “. . . I try to give the viewer something to which he will react subjectively. I believe these are highly emotional paintings not to be admired for any technical or intellectual reason but to be felt.”

The 13 artists included in Less Is More: Minimal Prints demonstrate that a geometric style is not necessarily sterile or empty. Although Minimal Art is sometimes criticized for concentrating only on design, art that is outwardly simple may be inwardly complex, and that which has the appearance of being easily executed may in fact be extremely hard won. Minimal Art, however reductive, is a personal expression.

Cleveland Art, July/August 2013