The Moon That You Wait for by Standing

- Blog Post

- Events and Programs

- Exhibitions

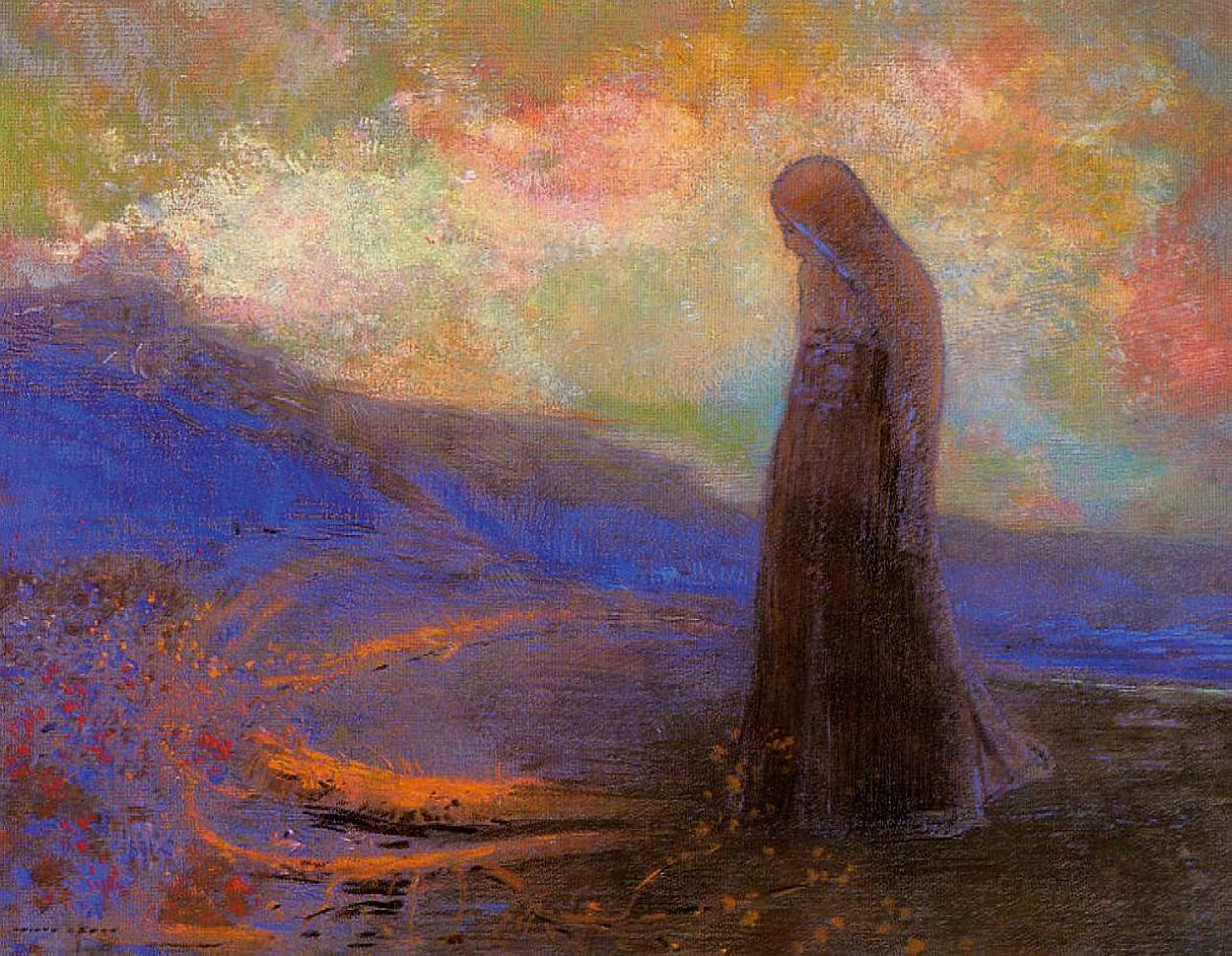

Reflection, 1900. Odilon Redon (French, 1840–1916). Pastel; 47.8 x 61.2 cm. Private collection

The Cleveland Museum of Art and Literary Cleveland (opens in a new tab) collaborated on a call for submissions following the theme of dark, fantastic, suspenseful, or just plain spooky writing inspired by the visionary art on view in the exhibition Collecting Dreams: Odilon Redon. This short story by Daleth Hall is our second blog finalist accompanying the upcoming co-hosted program, Noir: Writing Inspired by Odilon Redon TONIGHT Friday, October 29, from 7:00 to 8:00 p.m. at the CMA.

Although Reflection (below) is not in the exhibition, visitors to the museum can find similar intriguing artworks in Collecting Dreams: Odilon Redon.

This is the first country where I am the correct size. Doorways do not loom; chairs leave my feet on the floor. My body is no longer a mistake.

Now the mistake is my face. It’s incorrect.

My host mother, who is several inches taller than I am, puffs on a cigarette and says, “There used to be something you could do for that.” The orange dot flares and dims as she thinks. Through her smoke veil, she speaks in her own language, shining subtitles into my head: a line of yellow letters, the same color as her nicotined teeth. “I’m pretty sure the old lady who did it is still around. I’ll find out.”

My subtitles populate her sentences with phantoms: there used to be, you could do, I’m pretty sure. What she said contained none of those words. Phenomena simply exist here. Verbs unfold according to their nature.

I am draped in indigo cloth and placed on a tatami on my knees.

A window is open; it is raining, it is green. And in the next room I hear the murmur of the small crowd gathered for the first look at this season’s textiles. — industry people, who all know the thousand years of ways to weave cloth so deftly that it becomes like a piece of summer.

There are new ways too, new patterns. Each year, I’m told, the old lady and her daughters reveal them as if unveiling new words: not summer, not leaf-green or flower, but syllables equidistant to all three. Slant rhymes made of fabric.

She’s kneeling before me, our knees nearly touching, her face a spiderweb of wrinkles. In her hand, a wide, flat brush erases me. Her assistant, a man who must be almost as old as she is, shows in a mirror that my face is now just eyes in a blank white oval. When I close one eye, it disappears. In the next room, the audience claps.

A small black brush, tipped red, creates the contours of another face — in this country, shadows are red — and when she tugs at the indigo cloth, urging me to let it fall despite the fact there is a man, I’m surprised to find it’s not only my face that’s gone blank.

She is too. “Ah!” she says, and now the two of them are laughing, pointing at my body, shaking their heads. “I’m old,” she says, or Oldness is. “That was stupid,” or Stupidity was.

No nipples, no navel, no tone but bright white. Everything’s erased.

They shrug. They chuckle. The man blames himself, for handing her the wrong paint.

#

As the paint cures I become almost perfectly invisible: a heat haze, a shimmer.

Animals notice me. A tiny dog growls from someone’s purse. In a cat café, felines swirl around the legs of a chair that even to me, looking down, appears empty. I feel the caress of a tail against my shin. I don’t know whether they can see me or are just picking up my scent.

People only see me if they need something and are alone. A gray-haired tourist outside a hotel is weeping; a woman just stormed off after an argument in another language. I stand right in front of him — this is something I can do now — watching his shoulders shake in their suit jacket, the teardrops following the tracks that age has cut in his face. When he blinks, I see in his corneas silvery reflections that distill into a face. Not mine, or at least not the one I remember.

I say, “She’ll come back.” Or just: Returning. A pale ribbon of subtitles spirals from my mouth. As it curls into his ear, he smiles.

#

When I try to explain the problem — my invisibility — my host mother says, “Well, you don’t bother people anymore. She did you a favor.”

What she said was that bothering no longer happens. A circumstance meriting gratitude has come to be. My subtitles add placeholders, pronouns: chalk outlines shaped like people.

She’s annoyed that I haven’t paid her back for the old woman’s services.

#

I try to find the old lady. I’m looking for a tiny building near a tiny river where school children line up to feed ducks. On either side of her studio, I remember, were completely different businesses: a car-repair shop that only had room for one car at a time and a convenience store made of glass, where we went first, and I bought a snack — a fleck of salmon inside a triangle of rice inside seaweed origami inside a cellophane wrapper so expertly folded that it came off in one piece with a flick of my wrist.

I find her in her doorway watching the children. She recognizes my voice. When I explain the problem, she congratulates me: I’ve become a silver frame she can see the summer through. A prism refracting the riverbank’s flowers.

“But you erased me,” I say. “Can you bring me back? Or paint another self?”

Her face falls.

#

My host mother is furious that I disrespected the old lady’s work. When she opens her mouth a storm emerges, complete with lightning. It swirls larger, purple arms of cloud unfolding, filling the room. The raindrops are a silver haze, falling so hard they knock my yellow ribbon of subtitles to the floor.

It lies half-buried in mud. Rivulets of chalk are washed away.

#

It’s surprising how quickly I forget my own face, and forget being something other than a shimmer or a lens.

If you flew to a new country and your luggage was lost, so you roamed the cities naked yet nobody noticed, that might rhyme with this.

If you watched clouds taking the shape of an animal, then glanced down and read the animal’s name in a tree, where branches happened to cross and form letters.

A short while later, I remember that my body is mostly water: a raindrop in a storm.

A short while later, I pay my host mother back.

Daleth Hall received an MFA in fiction from the University of Michigan. Her short story “Glastonbury Tor” was a finalist in The New Guard Machigonne Fiction Contest and will be appearing in The New Guard this year. Two of Daleth’s previous stories were selected by New River Dramatists to be performed by professional actors on Clocktower, a New York City–based internet radio station. She was recently asked by a producer to turn her story, “Ophelia’s Landlord,” into a one-act play, which had a three-night run at The Players (opens in a new tab) club in Manhattan.