The Novel and the Bizarre

- Magazine Article

- Exhibitions

A focus exhibition looks at four 17th-century tondi by Salvator Rosa

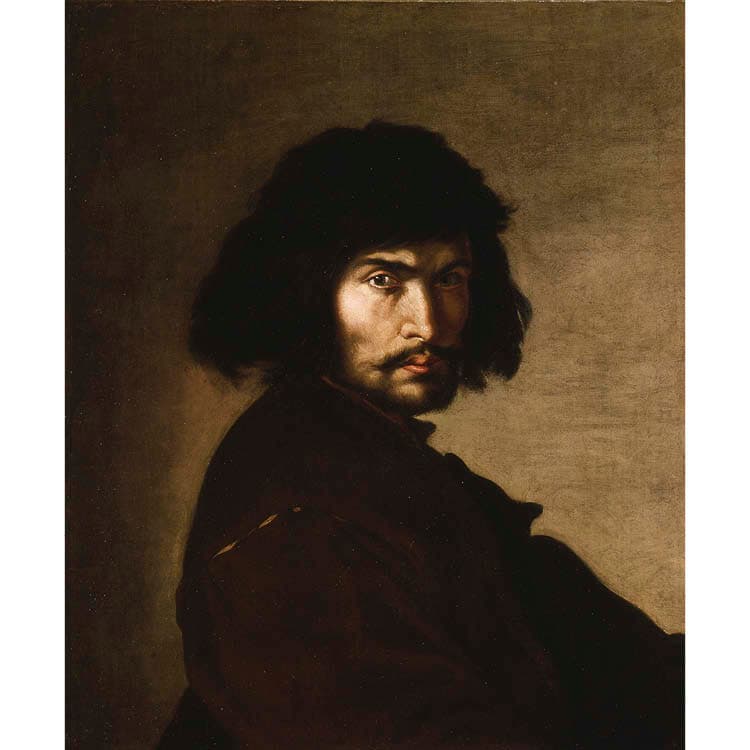

Self-Portrait, 1650s. Salvator Rosa. Oil on canvas; 75 x 62.5 cm. Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase, John and Rhoda Lord Family Fund, 66.191. Photo courtesy Bridgeman Images

The day after our yearly celebration of romance and chocolate, the Cleveland Museum of Art will evoke the more gruesome memories of Saint Valentine with the opening of a new exhibition, The Novel and the Bizarre: Salvator Rosa’s Scenes of Witchcraft. The Italian artist Salvator Rosa (1615–1673) was one of the most dynamic personalities of the 17th century, fiercely committed to his independence and originality and obsessed with promoting his reputation as a great painter of histories, philosophy, and morality. Rosa depicted numerous images of witchcraft during the 1640s, but the museum’s four tondi are thought to be Rosa’s first, painted around 1645–49. These unique creations not only reflect the contemporary and popular fascination with witchcraft throughout Europe, but also reveal Rosa’s novelty and the Florentine traditions of satire, burlesque, and the macabre. Presented in the Focus Gallery, this exhibition aims to unravel the cryptic symbolism of Rosa’s startling images and to articulate their role in fashioning Rosa’s unique and influential artistic personality.

Rosa grew up around Naples, absorbing the influence of the rustic and wild Campanian landscape and the artistic legacy of Caravaggio’s and Jusepe de Ribera’s dark naturalism. Educated at the Piarist school in Naples, Rosa was exposed to new discoveries in science, including those of Galileo, and his early contact with scientific circles influenced and spanned the majority of his career. In the studios of Francesco Fracanzano (Rosa’s brother-in-law) and Aniello Falcone, he was praised for his “spiritoso naturali,”his quick and clever wit. Rosa became known for his fresh and flickering landscapes and battle scenes that developed the “battle without a hero” genre pioneered by Falcone. Encouraged by celebrated artists such as Giovanni Lanfranco, Rosa moved to Rome around 1636 to bolster his artistic career in the center of the art world. He lived on the Via del Babuino near the Spanish Steps, in a house he adorned with large landscapes, visual calling cards for the emerging artist. Rosa quickly garnered fame in Rome not only for his artistic output but especially for his theatrical engagements, assuming characters of Neapolitan commedia dell’arte, like his legendary role of the brigand Pasciarello.

Scenes of Witchcraft: Day, Noon 1645–49. Salvator Rosa (Italian, 1615–1673). Oil on canvas; each 76.2 cm diam. Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund 1977.37

In 1640, perhaps prompted by a contentious rivalry with Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Rosa accepted Cardinal Gian Carlo de’ Medici’s offer to come to the court of Grand Duke Ferdinand II. During the first half of the decade, Rosa was closely allied with the court. His keen wit and theatrical persona made him a natural courtier, and he produced numerous works while thriving in the splendor of the Medici culture of festival and spectacle. But after becoming increasingly disillusioned with the hypocrisies and affectations of the court, Rosa retreated into erudite academies, most notably the Accademia dei Percossi. At the gatherings of the Percossi (in English, “The Beaten”), the literati of Florence congregated over elaborate meals to hear members recite poetry, discuss their ancient philosophical heroes such as Tacitus and Seneca, or enjoy spirited ethical debates and conversations about contemporary culture. These lively, convivial meetings also provided a place where the academy’s members could declare their distaste for a time so corrupt, and Rosa’s art and poetry would come to reflect their acerbic satirizing.

Witchcraft would certainly have been a subject embraced by the Percossi. The 15th and 16th centuries saw some of the most cruel and bloody witch-hunts, as Europeans blamed witches and their black magic for causing the Black Death, the horrific plague that decimated many countries’ populations. The production and proliferation of demonological texts and broadsheets printed with salacious and wicked acts added to the hysteria and dissemination of rumors and legends. This witch-mania, however, was never fully realized in Italy, and any real fear of witches had subsided during the 17th century. Nevertheless, the literary and visual culture of witches continued as a popular fascination, and their connections to magic, alchemy and new science, and mythology captivated the fantasia of the ever-inquisitive Rosa. With encouragement and patronage from his learned circle of friends, Rosa crafted fantastic, macabre, and clever witchcraft images and poetry throughout his time in Florence.

Ruins in a Rocky Landscape c. 1640. Salvator Rosa. Oil on canvas; 157.5 x 189.2 cm. Gift of Rosenberg & Stiebel, Inc. 1958.472

The exhibition is organized into three thematic and roughly chronological sections. The first presents Rosa as a brilliant landscapist. Through the CMA’s early Ruins in a Rocky Landscape (c. 1640) and drawings from the 1650s and 1660s, viewers can see how Rosa garnered fame for his wild landscapes, opposed to the strictly idealized and classicizing ones of Claude Lorrain. For centuries, Rosa’s critical fortune would rest on his reputation as the wild, proto-Bohemian painter of sublime landscapes, so memorably captured in the words of the 18th-century English art historian Horace Walpole: “Precipices, mountains, torrents, wolves, rumblings, Salvator Rosa.” Although Rosa would continue to paint landscapes—which became harsher, darker, and more savage throughout his career—he strove for a more distinguished and intellectual artistic persona.

Scenes of Witchcraft: Evening, Midnight 1645–49. Salvator Rosa (Italian, 1615–1673). Oil on canvas; each 76.2 cm diam.Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund 1977.37

The second section presents the four Scenes of Witchcraft, providing a unique opportunity to explore the paintings individually. Although we have no record of how this series originally hung in the palace of the Marchese Filippo Niccolini, their original owner, they have always been shown together as a whole. Each scene is paired with 16th- and 17th-century prints that draw out discrete themes from each tondo and its visual precedents. Day presents the “Dangerous Beauty” of witches who were both beautiful and destructive; Noon depicts the familiar grotesque and “Envious Hags” that arose from traditional personifications of Invidia (Envy); Evening brings us into the “Nightmarish Worlds” of the witches’ Sabbath, and the evil acts that occur there; and Midnight proves that women didn’t have all the fun: “Magical Men” were powerful sorcerers too. These four tondi reveal Rosa’s interest in literary and philosophical traditions, the antique, magic, witty satire, and an intense desire to create images of rare subjects.

Rosa’s return to Rome and his self-fashioned persona as an intellectual artist are the focus of the exhibition’s final section. Rosa arrived in Rome by February 1649, determined to cement his reputation as a painter of cose morali, moral and philosophical subjects. Showcasing extraordinary painted, drawn, and etched works from the 1650s and 1660s, this section shows how Rosa employed his virtuosity in various media to project his genius across numerous platforms. Most importantly, it also reveals how Rosa adapted the novelty and bizarreness of his Witchcraft paintings to his grand ambitions for his work in Rome, culminating in the brilliant and arresting Self-Portrait (on generous loan from the Detroit Institute of Arts) that gives a face to this noble, mysterious, and melancholic genius.

Cleveland Art, January/February 2015