That “Pang in the Night”: The (Unintentional) Evolution of Charles Burchfield’s Church Bells Ringing, Rainy Winter Night

- Blog Post

- Exhibitions

For the first time in nearly 20 years, visitors to the Cleveland Museum of Art can view Charles Burchfield’s 1917 watercolor Church Bells Ringing, Rainy Winter Night, featured in the exhibition Charles Burchfield: The Ohio Landscapes, 1915–1920. Although the striking image has attracted the attention of scholars, curators, and visitors alike over the past century, few know that it originally looked very different than it does today — and could have changed further still had the artist gotten his way.

A native of Salem, Ohio, Burchfield attended the Cleveland School of Art (precursor to today’s Cleveland Institute of Art) and spent intense formative years in Ohio before moving to Buffalo in 1921. In Church Bells Ringing, Rainy Winter Night, the artist used forms and symbols to express the fear he felt on stormy nights as a child.

In 1953, Church Bells Ringing was showcased in a major exhibition of Burchfield’s watercolors organized by curator Leona E. Prasse at the Cleveland Museum of Art. The painting had been donated just a few years before by Louise M. Dunn, who had studied with Burchfield at the Cleveland School (now Institute) of Art.

Burchfield was excited about the exhibition, describing it in a 1953 letter as “represent[ing] a phase of my work never before shown publicly.” He lent many works from his own collection and visited Cleveland to see the display.

Although he was pleased with the show, Burchfield noticed differences in Church Bells Ringing since he had sold it. A reddish tone he used in the church’s steeple had faded almost entirely, making the drawing predominantly gray.

Burchfield apparently contacted the CMA at that time and requested that the drawing — now part of the museum’s permanent collection — be sent back to him so that he could paint over the faded area, changing it from mauve to a deep blue. The museum’s then director William M. Milliken decided against sending the work back to the artist given its importance to the collection and the risk that Burchfield might permanently alter its appearance. In a journal entry from May 13, 1955, Burchfield described the conversation he had with Milliken, recalling that he had jokingly threatened to “sneak in some night and change it,” to which the director responded that he would “double the guards.”

In a catalogue essay for the 2010 exhibition Heat Waves in a Swamp: The Painting of Charles Burchfield organized by the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, and the Whitney Museum of American Art (opens in a new tab), (opens in a new tab) curator Cynthia Burlingham studied the watercolors that Burchfield most often used and found that he was aware that some of them would potentially fade.

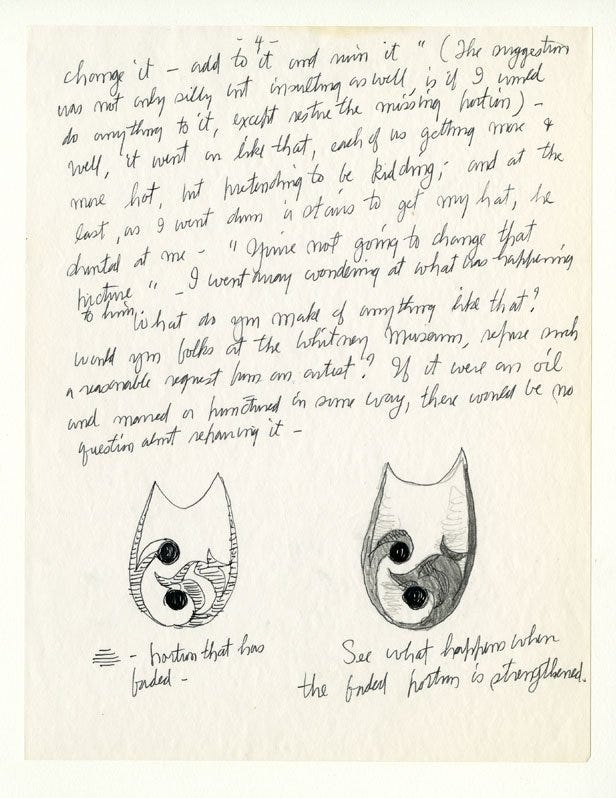

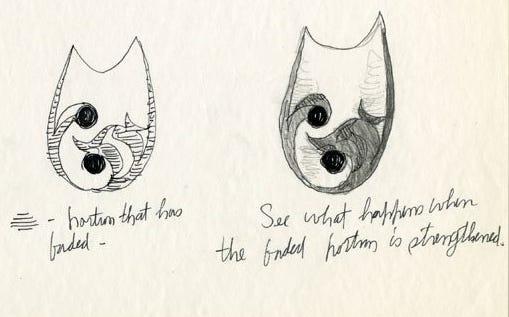

Burlingham also found details about Burchfield’s dissatisfaction with the discoloration of Church Bells Ringing in a letter that he wrote to Whitney curator John I. H. Baur in 1955 — he even included a diagram of how the work had changed.

Today, the tower of Church Bells Ringing remains unaltered, and probably appears as it did in the 1950s, with a predominantly blue and gray steeple. By limiting the drawing’s exposure to light, the museum’s conservation staff has controlled any further fading of the existing colors. Although the image has changed, it still captures — even a century later — the anxieties and fears Burchfield poignantly described in a 1929 letter as “[that] pang in the middle of the night.”

Charles Burchfield: The Ohio Landscapes, 1915–1920, Julia and Larry Pollock Focus Gallery, through May 5, 2019