Recovering Lost Histories of Pride

- Blog Post

- Events and Programs

Art reflecting the origins of Pride Month and its connections to the Black Lives Matter movement was discussed this week in the Cleveland Museum of Art’s online forum, Desktop Dialogues. Naazneen Diwan from the LGBT Community Center of Greater Cleveland and Nadiah Rivera Fellah, associate curator of contemporary art at the CMA, joined Andrew Cappetta, manager of collection and exhibition programs at the CMA. Their conversation has been edited for clarity and length. Watch the full Desktop Dialogue below.

Cappetta: I’d like to begin with an image taken by the photojournalist Leonard Freed in June 1970, of the Christopher Street Liberation Day March, what we can now consider the first Pride March. Today, many—though not all—think of Pride as a celebratory parade. However, its origin was as a protest to demand fairness and equity for the LGBTQ+ community—then called the gay liberation movement. This 1970 march commemorated the one-year anniversary of the Stonewall uprising of June 28, 1969, when police raided the Stonewall Inn, an LGBTQ+ nightspot in NYC’s West Village neighborhood. That night, the patrons of the bar—and many others who had repeatedly experienced police oppression—fought back.

Two people played an important role in the Stonewall uprising; their importance to LGBTQ+ movements has long been neglected, and I only learned of it, as a cisgender gay man, from knowledge passed to me by friends and elders. The two are Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera.

Johnson was at that first Christopher Street Liberation Day March (opens in a new tab). A Black drag queen, performer, and activist, she was a crucial part of the gay liberation movement and has recently gained more attention as part of the social media activism of the Black Lives Matter movement, especially in relation to Black trans lives and the call to end the violence that community faces. Johnson creates a link between the Stonewall uprising of 1969 and the social justice uprisings of today.

Like Johnson, Rivera was also an activist (opens in a new tab). She, too, was at Stonewall, and maintained her activism, especially for trans rights, throughout her life. Johnson and Rivera started the organization STAR, or Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (opens in a new tab). At that time, the term “trans” was not in use, so people like Johnson and Rivera used the term “transvestite.” (While Johnson never identified as trans, Rivera did later in life.) STAR advocated for their community and operated a home for other gender-nonconforming people, given that stable housing and jobs were regularly denied them.

BIPOC (Black, indigenous, and people of color) artists and activists continued to be central to the LGBTQ+ movement into the 1980s and 1990s. One of the more outspoken was Cuban-American artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres. We are lucky to have a work of his in the CMA collection.

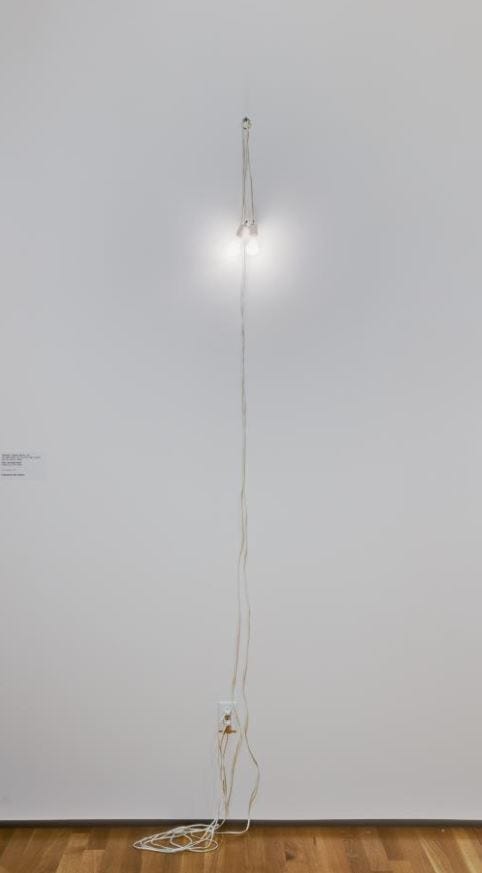

Rivera Fellah: I really love this work, Untitled (March 5th) #2. It is up in the contemporary galleries and can be seen when the CMA reopens. Gonzalez-Torres is part of the subsequent generation of LGBTQ+ activists who were primarily concerned with the AIDS crisis here in the US. His activism took place in part through his membership in Group Material, a group of conceptual artists working in New York from the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s that included Jenny Holzer—whose work is also on display in our contemporary galleries—Barbara Kruger, Hans Haacke, and others. Their work was really focused on progressive political causes. They would intervene in public spaces and usurp advertisements on billboards with their art. This was one pocket of art activism in the 1980s and 1990s.

On March 5, 1991, Gonzales-Torres lost his partner, Ross Laycock, to an AIDS-related death. In Untitled (March 5th) #2, Gonzales-Torres conjures a couple through a pair of gradually extinguishing lightbulbs, quietly commemorating his partner’s passing. Gonzalez-Torres’s own premature AIDS-related death five years later adds an additional narrative dimension to the work.

This work was part of a broader trend in history of pathologizing gay bodies—or visualizing those bodies as sick, ill, or dying, rather than strong, alive, or vibrant. Naaz, in the context of today’s conversation of recovering hidden histories and narratives, how can we rethink these bodies in other ways? What are some artists that you look to as the antidote, so to speak? Instead of memorials of death in the past, what artists exude life and propel us to think about a hopeful future?

Diwan: Yes, there are three artists I’d like to talk about who are showing Black and indigenous people with dignity and ingenuity.

Wangechi Mutu is a Kenyan-American artist who works in themes of Afrofuturism. Afrofuturism shows how artists who are Black, African, or of the African diaspora are reimagining and rebuilding new worldscapes through digital works and science fiction. They are imagining more than the conditions in this world. Mutu’s images refuel African women by portraying them as superhuman, mythical, fantastic.

You Are My Sunshine (opens in a new tab) imagines two women as cyborgs. In many traditional cultures, women were the bearers of the culture. And here these women are bedazzled with artifacts of their culture. With their arms linked, there is a transmission taking place. In the middle of them is a sunflower, which is a detoxifying agent, one that makes the soil fertile again.

Mutu also created Riding Death in My Sleep. It features a hybrid woman-alien figure who is looking boldly and defiantly at the viewer; she is perched on a planet with a field of mushrooms below her. Mushrooms often symbolize ancestors or death, so she literally stands on the backs of her ancestors—where she comes from. The figure is also in harmony with all these fantastic, mythical creatures that float around her. She is adapting in the wake of violence perpetrated on women’s bodies, and her white face is speaking back to Western beauty standards.

Rivera Fellah: Even the title is an antidote. This figure is totally self-possessed. There’s no sense that she’s ridden by death. Instead, it’s death be damned.

Diwan: Mutu puts a lot of different layers of materials in her work. She says it’s meditative for her. Art activism is not just about how the art is consumed or put in a gallery; the process itself is so important for the artist, particularly for an artist of color. There is something healing in just the creation of the art.

Next, I’d like to discuss the Jua Kali series by Kenyan artist Tahir Carl Karmali. Karmali explores themes of migration, labor, and displacement, much of which he has experienced himself. “Jua Kali” is a Swahili term—a pejorative term for people who would go into garbage heaps to repurpose things. But here we see Karmali reappropriating that term and honoring these people for being true artisans and creators.

Rivera Fellah: The collage of the elder figure in this series will be in our Second Careers exhibition. This is a photo montage of someone the artist admires, Wakanyote Njuguna, a playwright and artist. It’s a unique portrait, and it’s nice that a set of these will be in Cleveland soon.

Diwan: The third artist is Kehinde Wiley, who was born in Los Angeles. Wiley traveled the globe to take portraits of people of color. Sometimes the poses borrow from classic portraits, but Wiley uses a background and flora and fauna that are culturally significant to the subject.

Portrait of Geysha Kaua is meant to speak back to Paul Gauguin. There is a “third gender” concept in indigenous communities in North America and Polynesia. The third gender is not held to the binary concept of gender, and it’s not going to be defined, necessarily. Gauguin often objectified people like Geysha, to sell his art back to European collectors. But in this portrait, look at the bold stance. Geysha was a collaborator who chose the patterns and the pose to exhibit self-presentation.

Rivera Fellah: The Wiley portraits confront the idea of power and how it’s presented. To carry this conversation forward into the present day, it’s important to take what Naaz has shared about Black, trans, and queer brilliance and vibrancy and look around at images of Black, queer, trans, etc. bodies in public spaces. What are they doing, how are they carving out new spaces for themselves in a really exciting contemporary moment in public conceptions?

One great example is this viral image of two teenagers in Richmond, Virginia (opens in a new tab). Their names are Kennedy George and Ava Holloway. In tying a photo or action like this back to Felix Gonzalez-Torres—it’s also in the spirit of his generation—these girls are staging an intervention into public spaces otherwise reserved for racist monuments.

Desktop Dialogues take place every other week on Wednesdays at noon. Join CMA curators, educators, and other invited guests in a live online discussion about works in the collection that address issues people face today.