Scholarly Journal Elevates Conversation on Caravaggio’s Masterwork at the CMA

- Blog Post

- Collection

- Conservation

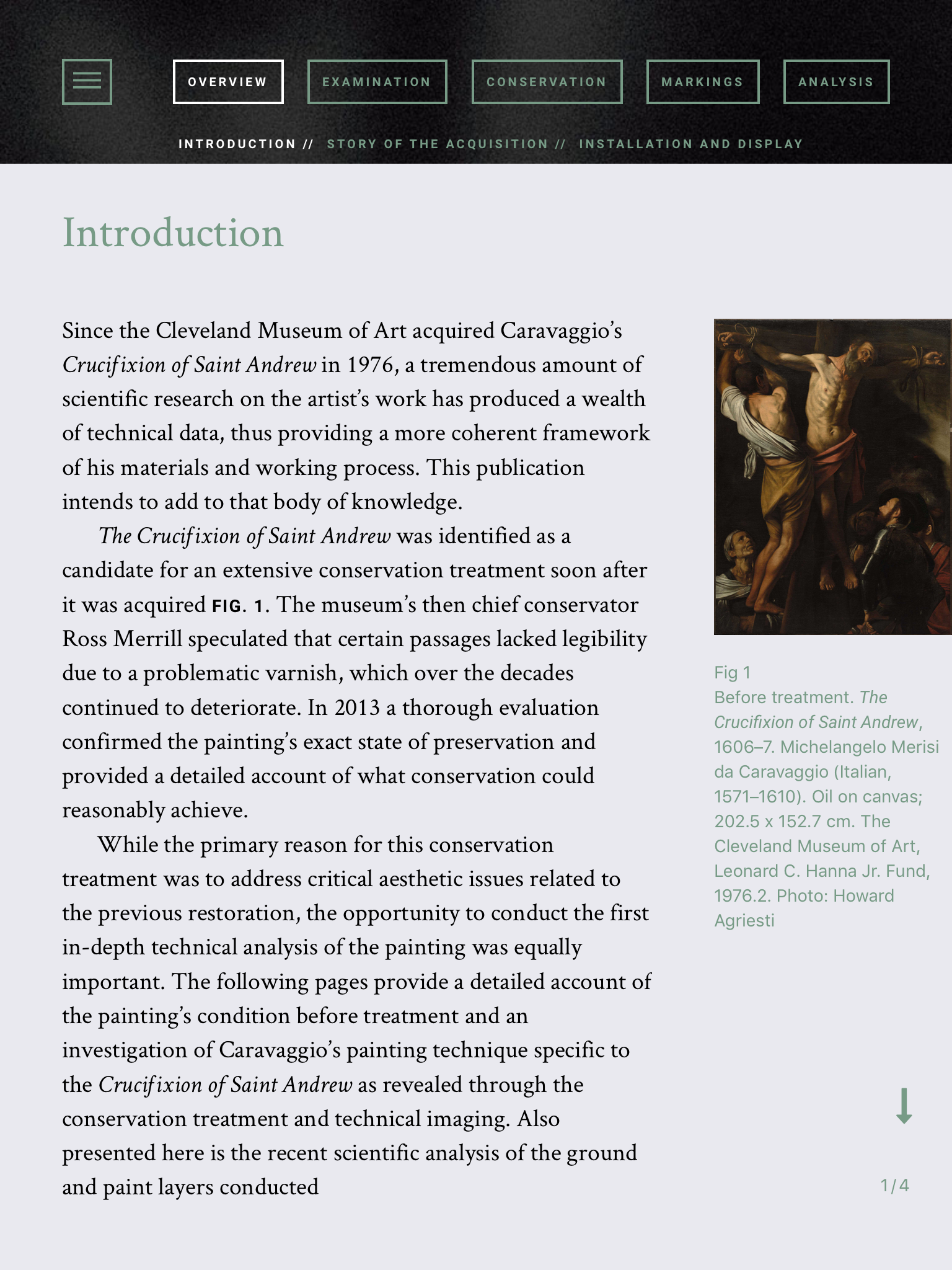

The Cleveland Museum of Art’s Crucifixion of Saint Andrew by Caravaggio is a masterpiece of baroque painting. It is one of only eight works by Caravaggio in the United States and the only altarpiece by the artist in America. Painted in Naples in 1606–7, the work was taken to Spain in 1610, where it likely remained for hundreds of years. The painting was acquired by the Cleveland Museum of Art soon after its rediscovery in the 1970s.

Just this week, this centuries-old painting graced the June 2018 cover of The Burlington Magazine (opens in a new tab), a prestigious monthly academic journal that covers the fine and decorative arts. Established in 1903, it is the longest-running art journal in the English language. Author Richard E. Spear took an in-depth look at Caravaggio and the Crucifixion of Saint Andrew. He asks two key questions in his article: are there autograph replicas (faithful second versions) of the Crucifixion? And what might scientific analysis of Caravaggio’s paintings add to this scholarly pursuit?

Featured in The Burlington Magazine (opens in a new tab) article is the CMA’s conservator of paintings Dean Yoder, who spent nearly three years studying Caravaggio’s working technique, cleaning and conserving the painting, and analyzing technical images.

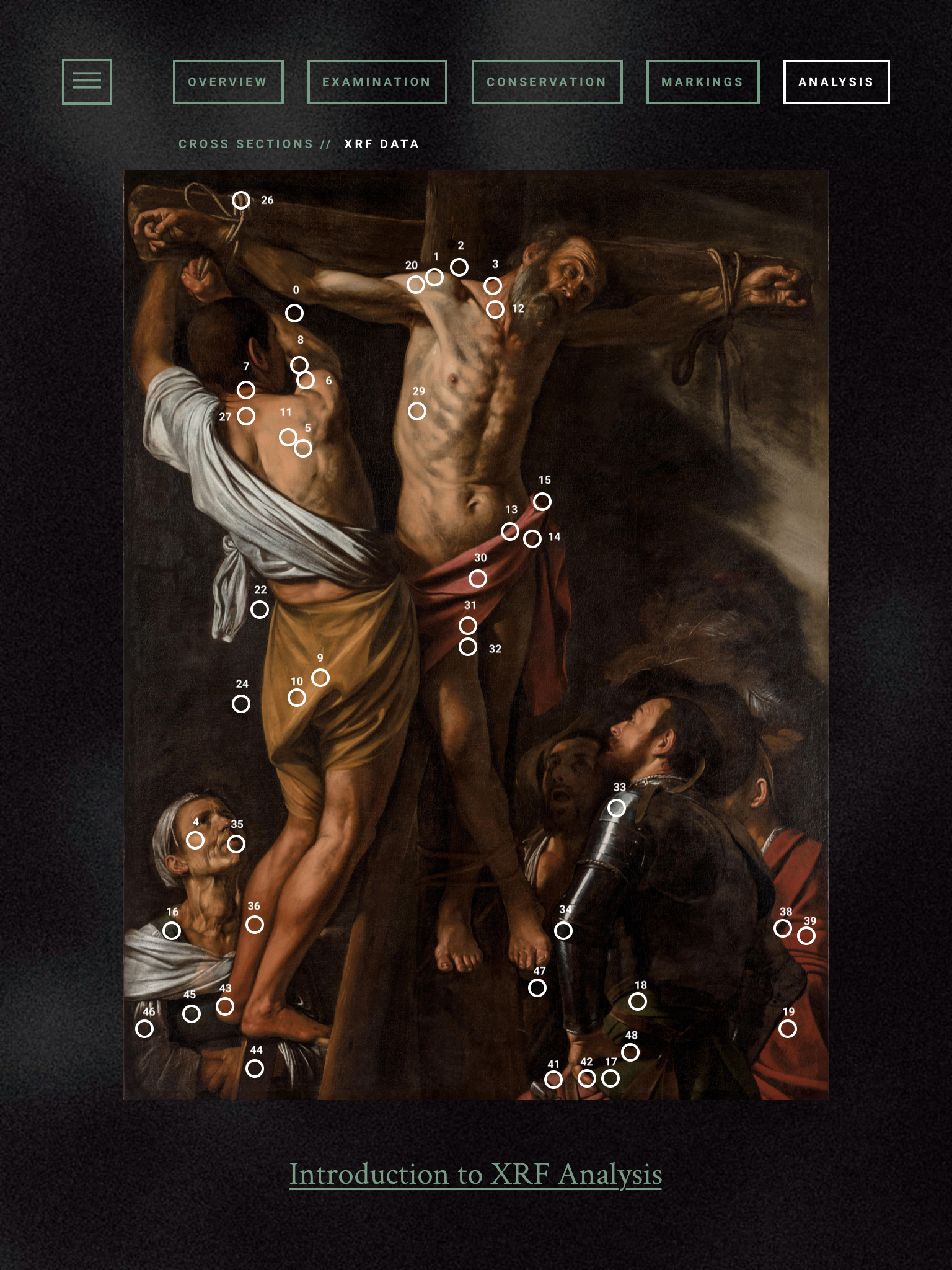

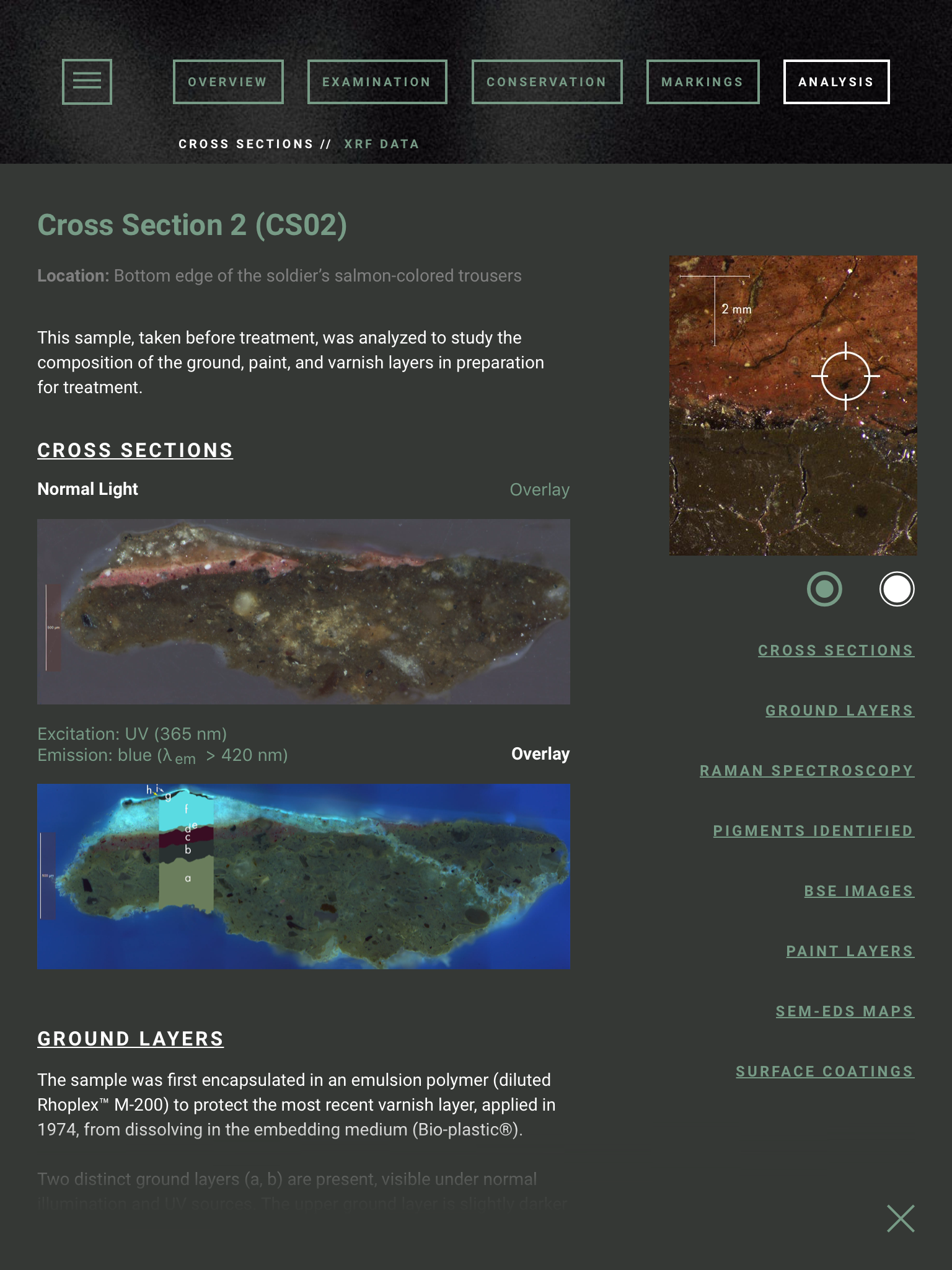

The discoveries made during this process are now shared in Conserving Caravaggio’s “Crucifixion of Saint Andrew”: A Technical Study, an interactive app (opens in a new tab) detailing the methods of analysis that Yoder used — including X-rays, pigment analysis, infrared reflectography, UV irradiation, Raman spectroscopy, and more — to illuminate aspects of Caravaggio’s working process and uncover details of the painting’s genesis and execution.

The Burlington article also features the scholarship of Erin E. Benay, PhD, Climo Assistant Professor of Renaissance and Baroque Art at Case Western Reserve University. Dr. Benay recently spent several years following the conservation efforts at the museum and authored Exporting Caravaggio: The Crucifixion of Saint Andrew (number 4 in the Cleveland Masterwork Series), published in 2017. Part of an ongoing focus series of books, Exporting Caravaggio is the first book-length publication to consider this understudied masterwork in its complex historical and geographic contexts, and to incorporate the findings of a recent conservation study in its assessment of the work.

In 2017, the Cleveland Museum of Art presented scholars and lay audiences alike with the unprecedented opportunity to make side-by-side comparisons between Caravaggio’s original painting and the “Back-Vega” version, one of the painting’s best-known 17th-century copies.

Right Image: The Crucifixion of Saint Andrew, 1606–1607, Caravaggio (Italian, 1571–1610). oil on canvas, Framed: 233.5 x 184 x 12 cm. Leonard C. Hanna, Jr. Fund 1976.2

We spoke with Dr. Benay to learn more about Caravaggio and his seminal painting.

CMA: Your work is described as “the first book-length publication to consider this understudied masterwork in its complex historical and geographic contexts.” Why has this masterwork been understudied and what is the significance of scholarly interest now?

Benay: Although Ann Lurie and Denis Mahon published a fantastic article about this painting when it was acquired by the CMA in 1976, there has been virtually no scholarship about the painting since that date. In my view, this is reflective of a general (though now-changing) dearth of scholarship about Caravaggio’s non-Roman years, and because this particular painting has a complex history beginning with its point of origin in Naples and its subsequent removal to Spain. It is the subject of renewed scholarly interest now because it has finally received the restoration treatment that it has long needed.

CMA: An article published in Case Western Reserve University’s The Daily (opens in a new tab) notes: “Professor Benay . . . is especially interested in the ways in which objects are manufactured, how they move through space and time, and in what ways they contribute to the production of knowledge and belief.” How does this statement relate to your studies of Caravaggio’s Crucifixion of Saint Andrew?

Benay: In my view, the Crucifixion of Saint Andrew is an especially interesting picture for two interrelated reasons: one is due to its history as a mobile object. Although it was undoubtedly commissioned to be an altarpiece in the palace of the Spanish viceroy in Naples, it did not remain there for long. Instead, the viceroy brought it with him to Spain when he left his job in Naples. From that point, the painting shifted from a locus of pious devotion to a subject of secular veneration. In turn, as I argue in my book, it contributed to the ways in which Caravaggio and his style became a commodity in the seventeenth century and beyond. Next, the surface of the painting has undergone numerous changes, damages, and erasures that may be better understood due to its recent restoration by CMA paintings conservator Dean Yoder. As a result, the study of this painting constitutes a unique opportunity to think about the ways in which objects were manufactured, and how their history as physical objects impacts their present-day interpretation.

CMA: What about this particular work drew you to such intense study, culminating in a book?

Benay: I have worked on Caravaggio for nearly a decade and so have long been interested in the ways in which his religious paintings could function as objects of both sacred devotion and secular fascination. I am a professor in the art history department at Case Western Reserve University and we participate in a joint doctoral program with the CMA. As a result of this unique relationship, I have excellent working relationships with curators and conservators at the CMA. When the 2012 restoration of the picture commenced, this offered an important opportunity to undertake a new, methodologically innovative art historical study of the painting and I was thrilled to be able to do so.

CMA: The Burlington Magazine focused its editorial content on the so-called “autograph replicas” and it talks about the side-by-side comparison between the CMA’s painting and the Back-Vega version we provided for our visitors last winter. How was this significant for scholarship and for public understanding?

Benay: The installation of the so-called Back-Vega painting next to the autograph Caravaggio original was a truly remarkable event for both the scholarly and general public. This comparison allowed viewers to contemplate how copies were made in an age before mechanical reproduction, to assess for themselves how this particular copy stacked up with the original, and to rethink what artistic “genius” and originality might have meant in the seventeenth century.

Furthermore, as Richard Spear explained in his Burlington article, this comparison enabled most specialists to arrive at the definitive conclusion that the Back-Vega painting is not by Caravaggio, despite some recent attempts to assert that it is. What I found especially exciting about this installation was listening to museum visitors’ responses to the two pictures: although they look nearly identical at the outset (a tremendous feat, given that the copyist could not use photographs or digital transfer processes), every single nonspecialist viewer that I spoke to easily recognized the hand of the “real” artist in the CMA’s painting by Caravaggio. How or why they could recognize this authenticity poses interesting philosophical questions about quality and connoisseurship that are central to the art market and to art historians alike.