Women at the Court

- Magazine Article

- Exhibitions

In the court of Maximilian I, a girl’s best friend might be courtly conduct manual

Morena Carter Exhibitions Coordinator

With the rise of princely courts during the 16th century, books outlining proper behavior and etiquette for women became popular. Baldesar Castiglione wrote one of the most widely read books on courtly conduct for both men and women: The Book of the Courtier, first published in Venice in 1528. Begun 20 years before, when Castiglione was a courtier at the Court of Urbino, it summarized widely accepted medieval standards of chivalry and cited humanist ideals valued by scholars and the nobility during the Renaissance. According to publication records, The Book of the Courtier was published across Europe during the 16th century; Francis I of France (ruled 1515–47) had it translated for his courtiers with the expectation of creating the model court Castiglione described. It is reasonable to assume that many of Europe’s rulers and noble families, including the Habsburgs, were at least familiar with Castiglione’s book and owned several conduct books. In fact, possessing them was a sign of noble standing or wealth.

The fortunes of most upwardly mobile noble families did not rest with the mothers and daughters, but with fathers and sons, and families invested in their sons by supporting them at school or at court. Daughters, it seems, were only politically useful if married into an important family, and women were usually described as the wife, daughter, or mother of a noteworthy man. To make a good marital match, it was thought that women required “training,” and much literature was available to advise them on their conduct and how best to protect personal and family honor, and especially chastity, while practicing the other arts considered customary for ladies at court, such as witty conversation and dancing.

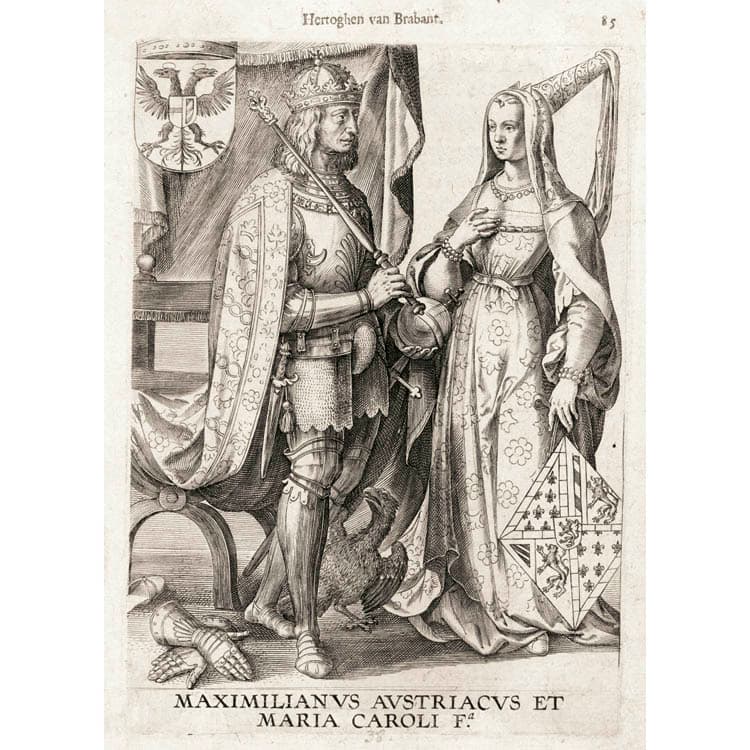

Maximilian I, who became Holy Roman Emperor in 1493, died before Castiglione’s book was published. However, records exist that allow us a glimpse into court life during his reign, and show that he was well aware of the requirements of a Renaissance court. His first wife, Mary of Burgundy, was heiress not only of the Burgundy region of France but also the Netherlands, which came under Habsburg rule with their marriage. In an image from Der Weisskunig, Mary is seen teaching her husband French in a tranquil garden setting where other courtly couples engage in conversation. This image portrays her as a valued counselor to her husband, who no doubt received an excellent education. We see Mary again with Maximilian in an engraving from the Chroniicke van de hertoghen van Brabant, this time formally portrayed, with Maximilian dressed as a strong ruler in armor and accoutrements of his power. This portrait, with the coat of arms of the Holy Roman Empire in the left-hand corner and an armorial shield of the House of Burgundy gracefully held by Mary, displayed their heritage and status as rulers over much of Northern Europe.

While the leadership of the Habsburg dynasty passed down the male line, many Habsburg women played powerful roles in promoting and securing the interests of the family. Margaret of Austria, daughter of Maximilian I and Mary of Burgundy, was regent for Charles V in the Netherlands in 1507 after the death of his father, Philip the Fair (Margaret’s brother). When Charles V left for Spain in 1519, so high was his regard for her ability to rule that he reinstated her as regent. No doubt her ability to act in the best interests of her family depended on her education and experience at her parents’ court.

Educated ladies-in-waiting were important assets to female rulers such as Mary and Margaret. Besides providing companionship and assistance with domestic responsibilities, ladies-in-waiting were important public figures at court. Girls sent to act as ladies-in-waiting at the Habsburg court had some formal education—at least enough to read and write. From the court at Turin (Italy) we know that one lady-in-waiting to the Duchess of Savoy, Lavinia Guasca, whose father, Annibal Guasco, groomed her for a court career from a young age, was educated as if she were a son. Although she did have brothers, her father turned to her to raise the family’s fortunes. When Lavinia was accepted as a lady-in-waiting at the court of Savoy at the age of 11, her father wrote a private rule book for her to guide her conduct in private and among other courtiers. Under the patronage of the Duke of Savoy she had the book published. here is a connection between Lavinia and the Habsburgs: the Duchess of Savoy was the Infanta Caterina, daughter of the Spanish Habsburg king of Spain, Philip II.

How broad an audience this conduct book had beyond the ducal family is hard to tell, but according to Peggy Osborn, the scholar who has provided the most recent research on Guasco’s life and work, Lavinia’s talents, morals, and virtues were known outside of Turin, and she did in fact make an advantageous marriage and used her courtly contacts to elevate her family’s position in Northern Italy.

The refinement of European courts and the rise of courtiers raised the level of education required for both men and women. However, while men could improve their chances of financial success and might enjoy a long career at court, most women were expected to return to the domestic, private sphere upon marriage, just as Lavinia did. To some degree, women from lower economic classes had more freedom to move between public and private spheres. The historian Steven Ozment has illuminated the life of one merchant family in the Holy Roman Empire. Through the letters of Magdalena and Balthesar Paumgartner, a merchant couple from Nuremberg whose marriage lasted through the second half of the 16th century, Ozment examines their relationship with each other, their son, and the larger community of Nuremburg. Magdalena is clearly in charge of domestic responsibilities, especially because Balthesar is constantly traveling throughout Germany and Italy for his work. However, Magdalena is also an important asset to Balthesar in his business, as an agent for the wares he procures for local clients, and she keeps the household accounts in order. From these letters we learn the Paumgartners believed that marriages should be prudently made between partners who will complement each other. And although Magdalena granted women a certain independence, she nevertheless recognized Balthesar as the undisputed head of their family.

Authors of conduct books described ideal manners for men and women, as well as the perfect court and home settings for their behavior. How closely their words were followed cannot be known, but from extant publishing records and library inventories we know that such books were widely available to nobles and wealthy classes across Europe, and were important in the conduct of court and domestic life.

Cleveland Art, April 2008