Art as a Reflective Practice

- Blog Post

- Events and Programs

Highlighting the Field of Medical Humanities in Celebration of Cleveland Clinic’s Centennial

Intro by Katherine Burke, Director, Program in Medical Humanities and Co-Director of The Art and Practice of Medicine at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine.

At Cleveland Clinic and Lerner College of Medicine, many physicians, nurses, residents, therapists, medical students, and other health care professionals turn to the arts to help work through challenging times. Medical humanities is a field that examines where the arts and humanities intersect with medicine, illness, and health. In this field, we not only look at illness memoirs or images of medicine to help us become better health care practitioners; we immerse ourselves in the arts and humanities to give us context and to help us both connect with each other and understand ourselves as we move through the joys and difficulties of working in health care. The vulnerable and insightful reflections that follow are examples of ways in which the people who work at Cleveland Clinic think about and use art as a reflective practice.

Whenever I visit the museum, I make it a point to visit A Woman’s Work (1912) by John Sloan. The painting depicts a woman in New York City hanging clothes out to dry, using pulleys and ropes strung between buildings. She leans over the edge of the fire escape to pin a white corset to the line. In the distance, we see another full clothesline with white petticoats and sheets blowing in the breeze, and we get the sense that this goes on and on and on, alley after alley, throughout the city. In his painting Sloan sanctifies this invisible work, hidden from most people’s view. It makes me reflect on the unseen labor of all those who work in health care. I think of the people who clean the rooms, who schedule appointments, who wash linens, who deliver meals. Without them, the hospital would grind to a halt. Their efforts are laregly unobserved, but those who see all that they do, day after day, know that the work is holy — and we are grateful.

Katherine Burke, Director, Program in Medical Humanities and Co-Director of The Art and Practice of Medicine at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine. She has worked for the Cleveland Clinic for ten years with extensive experience designing and implementing an arts-based research curriculum for medical school students.

In an age of the internet, where pictures of various artworks are easily accessible, Rashid Johnson’s Color Men (2015) is a piece that must be seen in person to truly appreciate it and do it justice. This remarkable work of art is layered in meaning. Soap (prominent medium in the work) is typically used to clean the body, but the black soap used here symbolizes the impossibility to remove one’s skin color. The piece is part of a series that explores the artist’s own anxiety and the anxieties experienced by young Black men. It successfully insinuates those emotions with the use of carved-out open and blank eyes. The lips resemble those of a mouth wired shut, wanting to scream for help but unable to, like someone whose shouts for mercy fall on deaf ears. Race-related disparities in health care are not new, but the shouts remain unheard. While efforts have been made to remove racial bias in our education and protocols in patient care, health care work encompasses people and all their biases impacting the well-being of other people whose life experiences differ from their own.

Anthony Onuzuruike is a medical student in the 2023 class at Lerner College of Medicine. Originally from Kansas City, Missouri, he did his undergraduate workat the University of Missouri-Columbia, where he double majored in chemistry and biology. He plans to pursue emergency medicine after graduation and has personal goals of working in policy with the hope to improve quality of life in communities around him and decreasing health disparities related to race and socioeconomic status. Anthony’s appreciation for art and its ability to speak to health care-related issues is evidenced by his publication in the February 2021 issue of the AMA Journal of Ethics titled “Black Determinants of Health.”

I have been drawn to Red Grooms’s Looking along Broadway towards Grace Church since the first time I viewed it, and always make sure to visit it when I am in the museum. The kinetic energy of this piece draws me in and reminds me of how much I love the bustle of working in the city at Cleveland Clinic. I love its deceptive simplicity, so much like the dioramas made in elementary school, when the creation of little scenes was a joyful exploration of imagination. As an art therapist, I see so many adults who have forgotten the delight of art making, experimenting with form, color, and shape. We know mindful immersion in a creative task can reduce anxiety, improve mood, and increase resilience. So instead of sinking into the winter blues, grab yourself a shoebox and some craft supplies to create your own little place to escape. Your heart and soul will thank you for it.

Tammy Shella, PhD, ATR-BC, is the art therapy manager for Cleveland Clinic Arts & Medicine. She holds an MA in art therapy and a PhD in psychology, with a specialization in health psychology. She has been with Cleveland Clinic for more than 23 years, initially working with behavioral health patients on both a general adult unit and the specialized Center for Mood Disorders, Treatment, and Research. In her current position, she created and continues to grow the medical art therapy program at Cleveland Clinic.

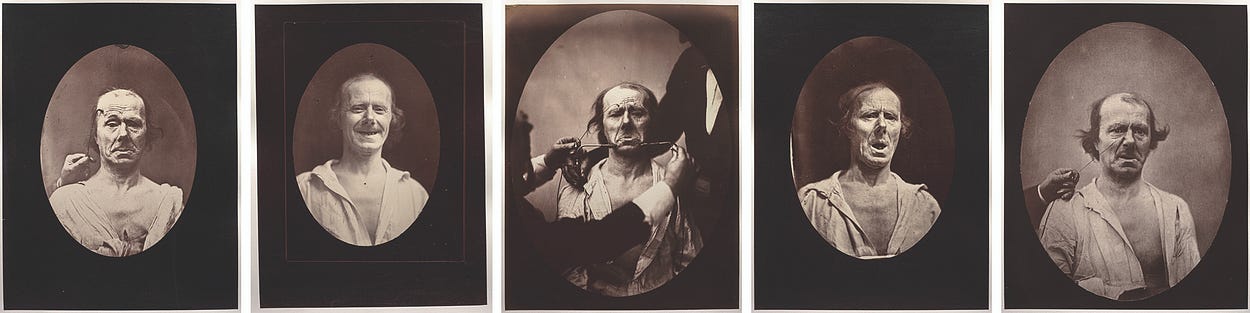

Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne, a great French neurologist in the 19th century, was known more during his lifetime for the electrophysiologic stimulation of muscles than for the specific neuromuscular disease (Duchenne muscular dystrophy) that bears his name today. These five Duchenne photographs from the museum’s collection, taken from a published treatise on facial expression, Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine (opens in a new tab) (The Mechanism of Human Facial Expression), are documentation of electric stimulation of individual muscles in various combinations. This was undertaken in the relative infancy of photography and represents an early photographic depiction of medical research. This work resulted in his theory that a genuine smile involves the muscles around the eyes (orbicularis oculi) in addition to those that lift the corners of the mouth (zygomaticus major and minor.) This expression of sincerity (eyes crinkled) is still known as a Duchenne smile, though there is some evidence it can be faked.

He was primarily interested in the idea of facial expression as a sort of snapshot of the soul, a Creator-given nonverbal language. The photographs themselves are at once bizarre and unsurprising. Medicine can be a macabre and disturbing pursuit. But these images strike me as (very) human, if clinical, and have always fascinated me.

Lainie K. Holman, MD, MFA, is the chair of pediatric physical medicine and rehabilitation at Cleveland Clinic Children’s Hospital for Rehabilitation. She received her medical degree from the Medical College of Ohio in 2002 and completed a combined residency in pediatrics and physical medicine and rehabilitation at Cincinnati Children’s in 2007. She is board-certified in pediatrics, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and Pediatric Rehabilitation. She also completed an MFA at Goucher College in 2011.

Want more? Drop by the recently opened FREE exhibition Derrick Adams: LOOKS on view in gallery 230. Adams’s paintings, which are about recognizing and respecting individual expression, directly address representation and visibility as conduits to empathy. The exhibition is a collaboration between Cleveland Clinic and the Cleveland Museum of Art in celebration of Cleveland Clinic’s centennial (opens in a new tab). Both institutions share a deep commitment to the value that all people need to see and be seen with empathy, and each organization contributes to that goal through art.