CMA’s Ingalls Library and Museum Archives Joins International Effort to Write Women into Art History

- Blog Post

- Events and Programs

- Ingalls Library and Museum Archives

Did you know that less than 10 percent of Wikipedia editors are female (opens in a new tab)? It’s a situation that many believe leads to bias regarding what is featured in the online encyclopedia.

For five years running, galleries, museums, libraries, and other cultural institutions around the globe have joined forces to host day-long Wikipedia edit-a-thons to redress this situation in relation to women in the art world. The edit-a-thons are scheduled in March through Art+Feminism (A+F) (opens in a new tab) to coincide with International Women’s Day (opens in a new tab), held annually on March 8.

This nonprofit group invites participants to promote women artists on Wikipedia by updating existing entries or starting new ones from scratch. The aim is twofold: to push back against discriminatory or nonexistent entries about cisgender and transgender women and to empower women as editors, although all who respect feminism are welcome to participate. A+F has become a force to be reckoned with, having received press coverage from Artforum (opens in a new tab), the New York Times (opens in a new tab), the New Yorker (opens in a new tab), and others, in bringing these issues to light.

One of the A+F founders, art librarian Siân Evans, used to coordinate a special interest group for the Art Libraries Society of North America (opens in a new tab) about women and art. At a recent conference, Evans shared that every year, members of the group would meet and bemoan the lack of exposure for women artists and feel energized liaising with like-minded professionals. Frustratingly, they would return to their workplaces without noticeable change taking place. So in 2013 Evans and three friends — Jacqueline Mabey, McKensie Mack, and Michael Mandiberg — formed A+F.

The need for more exposure for women artists has long been recognized. In 1971, the late art historian Linda Nochlin asked in an ArtNews article (opens in a new tab), “Why have there been no great women artists?” Her question remains so relevant that it appeared verbatim on a shirt on the Paris runway in last fall’s Dior collection (opens in a new tab), with audience members receiving copies of the article.

Before the publication of this revolutionary article, the knee-jerk response had been to hail examples of under-recognized artists, an impulse that hasn’t dissipated. For example, Frida Kahlo’s status has been elevated by Madonna (opens in a new tab), a collector, and filmmaker Julie Taymor. The more constructive way forward, in Nochlin’s view, is to recognize and dismantle barriers to female artists’ progress. Given that Nochlin was writing during feminism’s second wave, and if you’re questioning whether impediments for women artists still exist today, witness the #MeToo movement gaining momentum in the art world.

Wikipedia edit-a-thons may appear to just even the score by churning out entries about women artists; however, this is not the case. For example, edit-a-thon facilitators are asked to create a safe environment in their introductory comments by acknowledging alternatives to the gender binary of male/female and welcoming participants to state their preferred gender pronouns. Also, edit-a-thons are often accompanied by related programming that examines institutional bias. For example, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York — the nucleus for the project — the 2018 edit-a-thon began with the discussion “Careful with Each Other, Dangerous Together,” focusing on “the relationship between structures of inequality and structures of the Internet, the affective labor of Internet activism, and creating inclusive online communities. (opens in a new tab)”

After I delivered a presentation in January to the Womens Council of the Cleveland Museum of Art about trailblazing women in the CMA’s collection, our new Reference and Scholarly Communications Librarian Beth Owens noted that not all of the women I highlighted had Wikipedia entries. In short order, we committed to partner with Kelvin Smith Library at Case Western Reserve University (opens in a new tab) to plan edit-a-thons for the same day, March 7. With a tight timeline, I was able to draw on my experience of co-organizing an edit-a-thon at a nonprofit gallery in Canada the year before I arrived at the CMA.

In Canada we focused on regional artists who received grants; here we decided to make the CMA’s permanent collection our focus. Owens whittled down the long list of artists I had originally compiled, and Leslie Cade, director of Museum Archives, recommended permanent collection artists who had also exhibited in the May Show — an annual exhibition of Cleveland artists held by the CMA from 1919 to 1993.

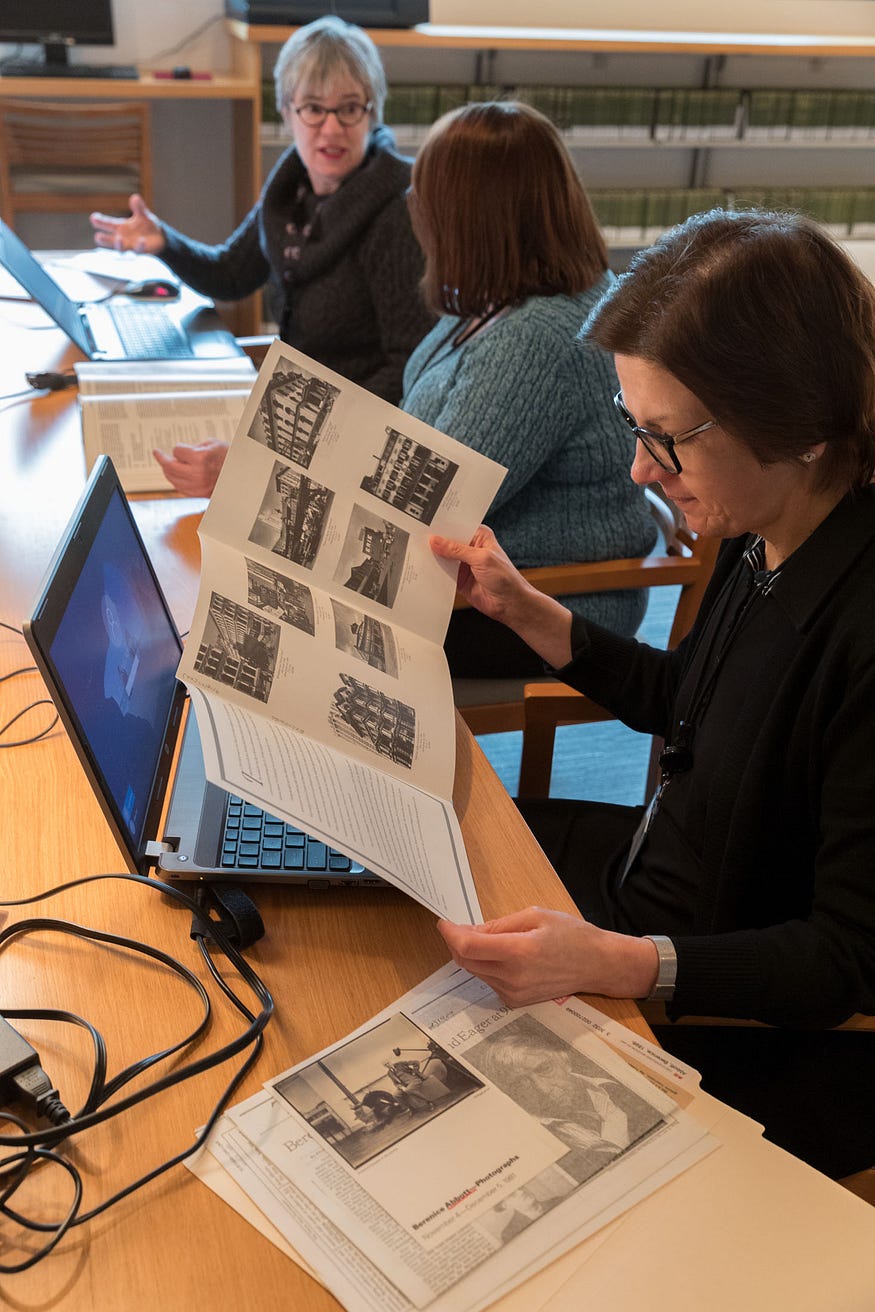

When participants arrived at the Ingalls Library and Museum Archives on March 7, they selected an artist from our short list, grabbed related research materials that had been provided, and decided to work solo or collaboratively. Owens commented that the collaborative approach was a joy to observe, with participants helping one another interpret content and navigate the sometimes tricky interface of Wikipedia. Lou Adrean, Head, Research and Programs, described hunting down obscure details as challenging, but energizing.

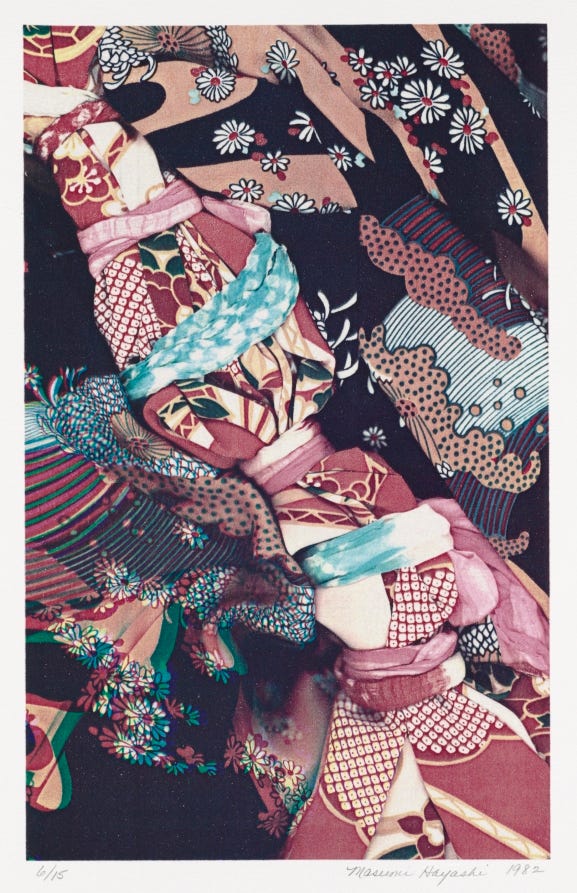

There were many noteworthy exchanges. For example, high school student Christina Popik recounted her mother’s memories of Cleveland photographer Masumi Hayashi, and Womens Council volunteer Mary Ann Conn-Brody said with delight that she felt like she was bringing the artist Anna Claypoole Peale to life. Over the course of the day, 11 editors wrote about 16 artists, collectively adding more than 3,000 words to the growing pages of women artists.

The edit-a-thon focused on the following female artists:

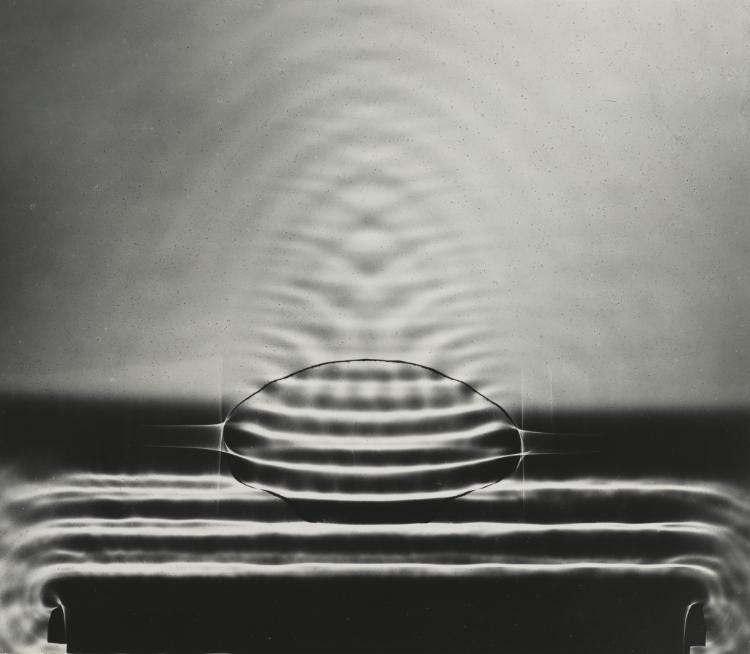

Berenice Abbott, photographer (opens in a new tab)

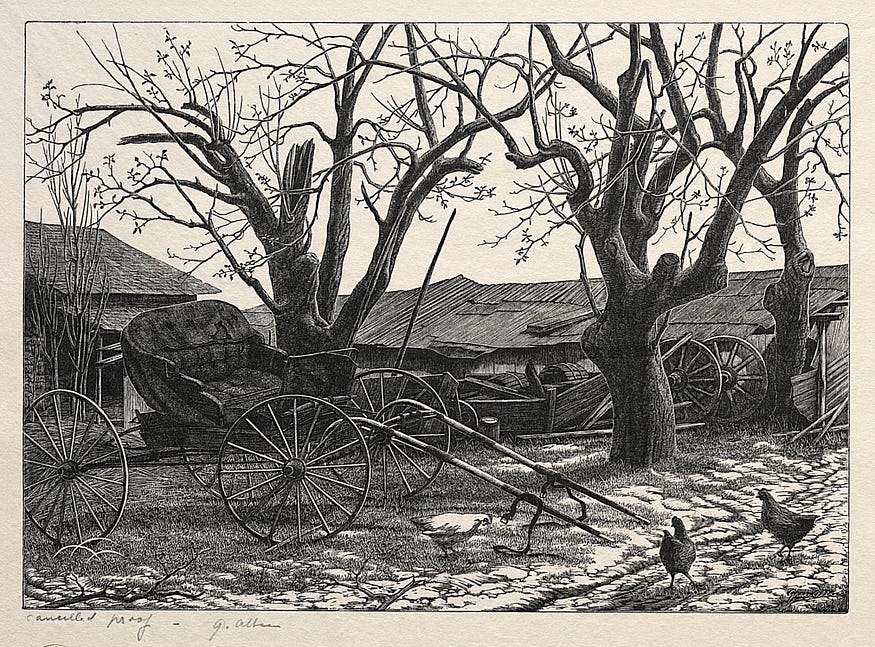

Grace Albee, printmaker, draftsperson (opens in a new tab)

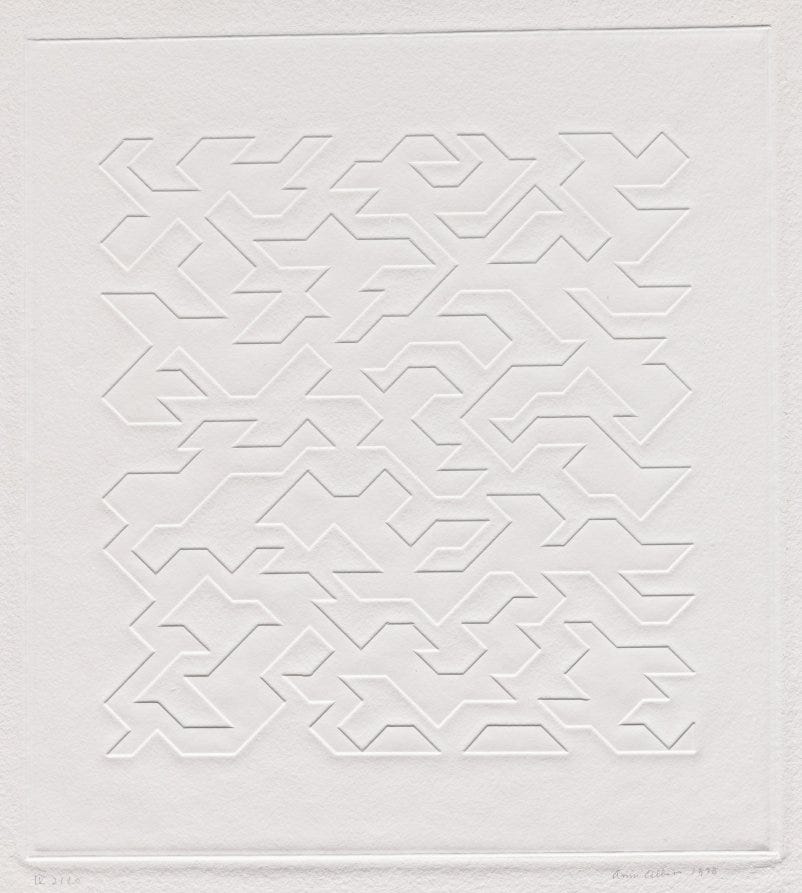

Anni Albers, printmaker (opens in a new tab)

Diane Arbus, photographer (opens in a new tab)

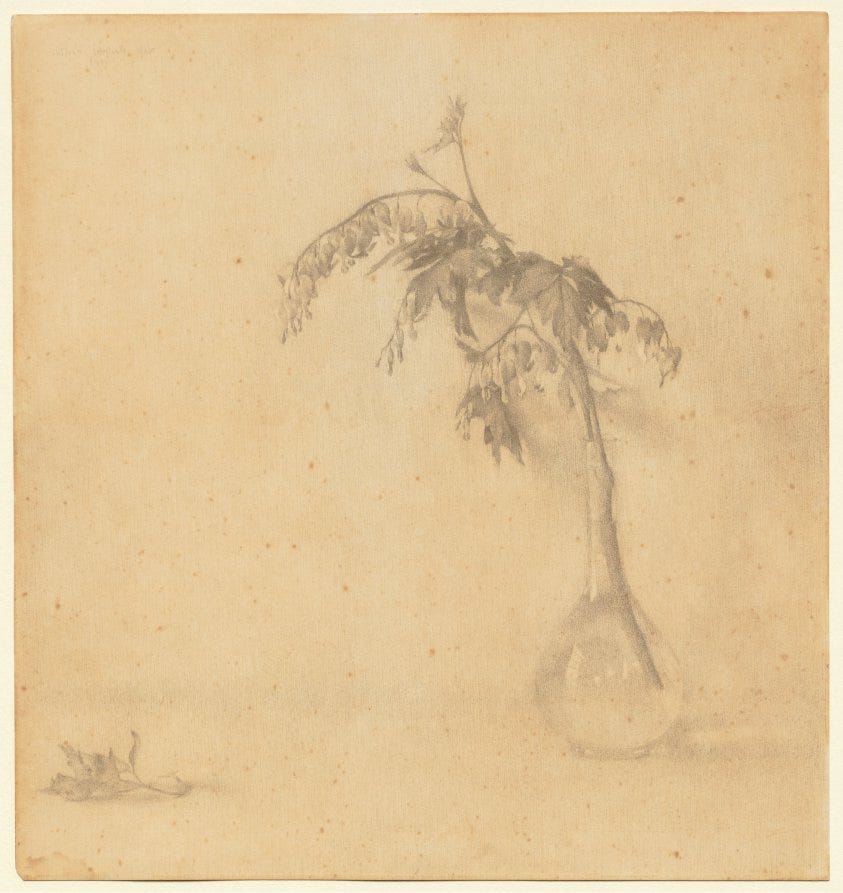

Lilian Westcott Hale, draftsperson (opens in a new tab)

Masumi Hayashi, photographer (opens in a new tab)

Jill Krementz, photographer (opens in a new tab)

M. Louise McLaughlin, ceramicist, decorative artist (opens in a new tab)

Inge Morath, photographer (opens in a new tab)

Anna Claypoole Peale, portrait miniature painter (opens in a new tab)

Ce Roser, printmaker (opens in a new tab)

June Schwarcz, enamelist, metalworker (opens in a new tab)

Judith Shea, printmaker (opens in a new tab)

Betty Woodman, ceramicist (opens in a new tab)

The Ingalls Library and Museum Archives thanks the Wikimedia Foundation for its support.