Drawing on Inspiration: Teaching Artist Adrian Eisenhower Discusses the CMA’s Michelangelo Pop-up Drawing Lounge

- Blog Post

- Education

- Events and Programs

- Exhibitions

The CMA’s blockbuster exhibition Michelangelo: Mind of the Master invites visitors to see more than 50 drawings by one of history’s greatest artists. In the interview below, Jennifer DePrizio, director of interpretation, talks with Adrian Eisenhower — the teaching artist in the Michelangelo Pop-up Drawing Lounge — about his thoughts on drawing and Michelangelo.

The exhibition Michelangelo: Mind of the Master provides a glimpse into the working mind of the artist through his drawings. Looking at Michelangelo’s drawings is like looking over his shoulder. Illustrating the connection between the artist’s hand and his thinking, the drawings mark a critical stage in the planning and development of all of his major works. Through drawing we see him working out an idea by thinking through compositions and sculptural forms. We see firsthand that drawing is essential to artistic practice.

With this in mind, the Interpretation team felt it was important for visitors to have an opportunity to try their hand at drawing. To that end, each Sunday and Tuesday for the run of the exhibition, we transform the Parker Hannifin Corporation Gallery, on the first floor of the museum, into a drawing studio. I recently sat down with Adrian Eisenhower, the teaching artist for this space, to talk about drawing and Michelangelo.

Jennifer DePrizio (JD): The big idea of the exhibition Michelangelo: Mind of the Master is that drawing is essential to artistic practice. I know that representational drawing is something you are particularly passionate about, especially as the founder of Walton Avenue Atelier. What is it about drawing that is so compelling to you as an artist and teacher?

Adrian Eisenhower (AE): I believe that drawing is fundamental to artistic practice, even if working toward nonrepresentational or conceptual purposes. While drawing we learn to see, think, and act in a visual language. Through drawing we enter and participate in a world of images.

I especially enjoy the pliability of drawing. I can use it to generate ideas or to fully realize a singular vision. Beyond developing fine motor skills, I have expanded my imagination, cognition, and confidence through drawing.

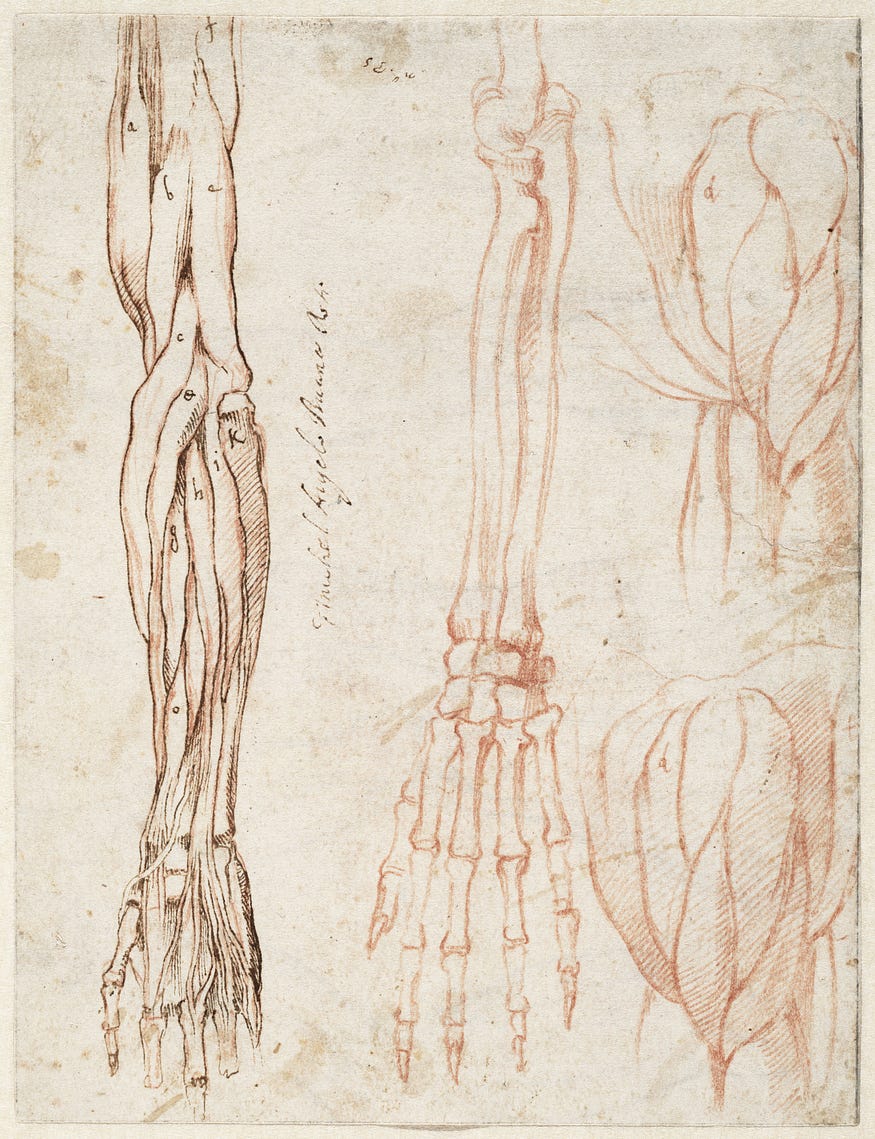

JD: When we first met to talk about this project, you showed me a drawing of a forearm that was very similar to one of the drawings in the exhibition. Have you always had an appreciation for and kinship with Michelangelo?

AE: Yes, I have always held an appreciation for Michelangelo, especially as a younger artist. I remember how his work kindled a type of wonder and spirit of adventure. I have enjoyed revisiting these feelings during this exhibition.

I was working from a cadaver around the time that I showed you the drawing of the flayed forearm. I was certainly aware that Michelangelo studied cadavers. There are also American artists who have a tradition of working closely with the human form, notably 19th-century realist painter Thomas Eakins and contemporary artist Michael Grimaldi. The figurative artwork that I find most compelling was and is made with a deep understanding of anatomy. Of course, all of this probably stems back to what happened in Florence and Rome during the Renaissance.

JD: While in the lounge you’ve been making copies of some of the drawings in the exhibition. What is this experience like for you? What are you learning about Michelangelo from this process?

AE: In the past, I benefited immensely from making copies of master drawings and paintings. From a technical point of view, the act of copying helps me unpack the construction method of an artist. It is a kind of reverse engineering. Copying is also a form of communication with the artist. They poured themselves into their work. Their work is where we can find them.

JD: And why do you think we are still so compelled by Michelangelo’s drawings today?

AE: Like Shakespeare, Michelangelo invented a vocabulary to describe different worlds — biblical, historical, contemporary. Michelangelo’s drawings give us an opportunity to look over his shoulder as he is developing ideas and the vocabulary to express them. I think it is the directness of this transmutation — from idea to imagery — that gives his drawings such intensity. They remain at the point of conversion from one state to another.

Of course, many of us have also been told from a young age that Michelangelo’s work is beautiful or important, for example. It is difficult to not look at his work through a lens of Eurocentrism and attending values. Objectivity here is very difficult.

JD: The drawing lounge is designed as a space for any visitor, regardless of their skill level, to sit at a drawing horse and try their hand at it. What advice do you have for the person who says, “I can’t draw.”

AE: I think of drawing as a practice, not an end product. The drawings by Michelangelo offer insight into a process that for social, political, and aesthetic reasons continues to reverberate today. The legacy of Michelangelo should not crowd out our own ability and enjoyment of a drawing practice. Try to reframe what drawing is if you think you cannot do it.

Adrian Eisenhower fell in love with Cleveland when he moved here in 2013. He grew up along the Hudson River, however, and will always appreciate the bucolic appeal of the Hudson valley. He earned his MFA in painting from Savannah College of Art and Design and has studied at Studio Incamminati, the Bay Area Classical Artist Atelier, the Grand Central Academy, and the Aegean Center for the Fine Arts. Eisenhower was a 2017–18 teaching fellow at the Cleveland Museum of Art. In 2017 he founded Walton Avenue Atelier, a collaborative space in Cleveland for the study and practice of representational art. Eisenhower teaches art at Pep Hopewell.