Gold Needles

- Magazine Article

- Exhibitions

Celebrating the stunning embroidery of anonymous Korean women

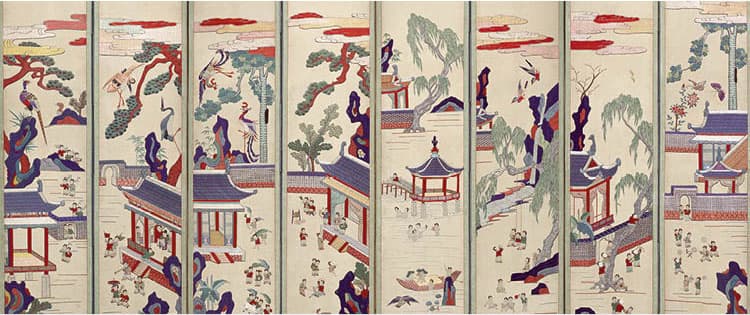

One Hundred Children at Play (detail), early 1900s. Korea, Joseon dynasty (1392–1910). Ten-panel folding screen; embroidery on silk. Seoul Museum of Craft Art, 2018-D-Huh-0001

In partnership with the Seoul Museum of Craft Art, the Cleveland Museum of Art presents Gold Needles: Embroidery Arts from Korea to celebrate the textile arts of Korean women during the later years of the Joseon dynasty (1392−1910). At that time, when the conservative interpretation of neo-Confucian teachings became mainstream, women, regardless of their social and economic status, increasingly faced rigid restrictions in all aspects of daily life. However, the anonymous women artisans showcased here developed their technical expertise and used their creative inventions as powerful tools to define their cultural identities and to promote awareness of the constraints on female expressivity.

Most of the pieces on loan to the exhibition and now in the collection of the Seoul Museum of Craft Art once belonged to Dong-hwa Huh (1926−2018) and Young-suk Park (b. 1932). The couple, who shared a passion for the preservation and presentation of Korean textiles, donated their entire collection to that museum in 2018.

Featuring exuberantly bright colors and bold geometric patterns, wrapping cloths called bojagi (pronounced bo-jah-ki) were used to pack and store items such as clothing, bedding, and gifts. Jubilant arboreal patterns, the most common design in the selected examples, symbolize eternal conjugal happiness, evoking a tree of blissful marriage life. With the help of her mother and aunts, a bride-to-be would laboriously embellish silk or cotton cloth with colorful thread.

The embroidered wedding gown hwarot shows how 19th-century Korean women’s aesthetics were sharply different from monochrome ink painting, the most prominent male-centered art form at that time. The gown’s red satin silk surface is lavishly embellished with colorful silk threads that form various decorative images, including peonies, butterflies, lotus flowers, a pair of white cranes, and phoenixes. Yet the bridal gown does not attest to a life of luxury. Traces of repairs, trimmings, and patchwork reflect Joseon-period women’s commitment to the neo-Confucian aesthetics of frugality and modesty. This gown was acquired by Langdon Warner in Korea on behalf of the CMA in 1915. Given its current condition, it must have served for at least 20 or 30 years as an important resource for a working-class community.

Also on view are various sewing tools like thimbles and rulers. The selected set of colorful embroidered thimbles, worn on a woman’s index finger, features various decorative patterns: fingerprints, zigzags, half circles, flowers, butterflies, and birds. The size of each thimble is small, yet its range of stitches is great.

While thimbles, pouches, pillow decor, and rank badges were created by amateur embroiderers, multipanel folding screens on view highlight royal embroiderers’ sophisticated artistry and professionalism. Girls as young as seven and eight from the lower working class were recruited to the royal embroidery studio. The collaboration between female embroiderers and male painters was fostered to create the finest picturesque embroidery. The textile is based on a court painter’s design that female embroiders used to accurately render a shining set of bronze vessels. During that same period, men also found joy in embroidery, not only for creative pursuits but also financial success. The city of Anju in Pyongan province, known for its high-quality silk manufacture, emerged as the center of embroidery products by men. Despite their high price—the cost of a large-scale embroidered Anju screen was equivalent to that of a house in downtown Seoul—Anju screens were one of the most sought-after luxurious commodities. On view in the exhibition, One Hundred Children at Play is an excellent example of such a screen.

In each panel, boys are engaged in various activities, such as swinging, wrestling, boating, and archery. Having many children, particularly boys, was advantageous in Korean agricultural society, explaining why an image such as this became a symbol of blissful prosperity. Nevertheless, bearing as many male children as possible was one of numerous pressures placed on women in the patriarchal Korean society. Those who could not deliver such expectations were socially condemned as having committed one of the “Seven Evils for Expulsion”; some were even forced to divorce. Such pressure, however, never transcended strong parental love. The text below is part of a letter written by elite politician Kim Chang-hyop (1651–1708) to his daughter Kim Un (1679–1700), who died of complications in childbirth at age 21.

"Everyone wishes for fewer girls and more sons; this perhaps is common sentiment. I had five daughters and one son, but I loved you as if you were the only daughter I had. This was because of your superior intelligence, understanding, and knowledge. You were not an ordinarily talented young lady. . . . Your son is growing up to become a splendid fellow. Whenever he visits, I stroke him and hug him as if I am seeing you. . . ."

As testified in Kim’s letter, diverse perspectives existed within the mainstream Korean patriarchal culture, and thus they also did in traditional Korean embroidery. Gold Needles invites us to explore the issues of gender and socioeconomic complexity concealed beneath the colorful embroidered works.

Cleveland Art, March/April 2020