The Hinson Perspective

- Magazine Article

- Collection

- Ingalls Library and Museum Archives

- Staff

The retired curator of contemporary art and photography recounts a few decades of life and work

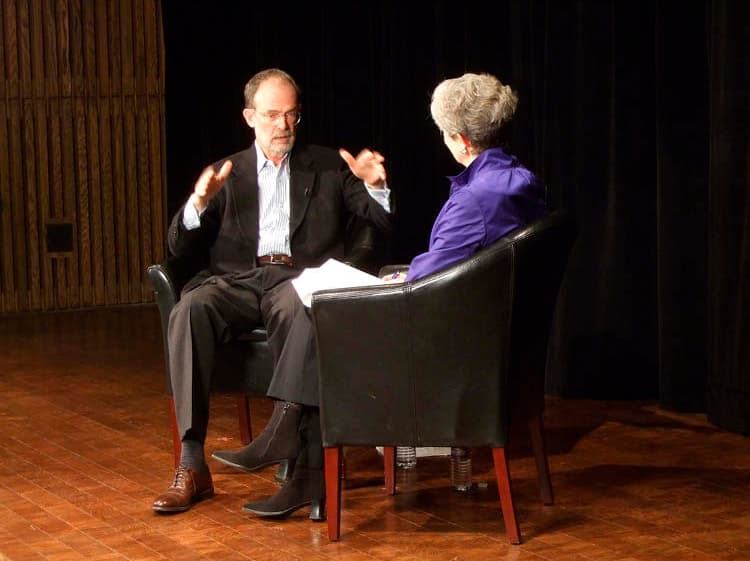

Tom Hinson Interview by Katie Solender

At the end of last year, Tom Hinson retired after 38 years at the Cleveland Museum of Art as a curator in contemporary art and later as curator of photography. In February his longtime colleague Katie Solender conducted a series of interviews, totaling four hours, during which Tom shared thoughts about his time at the museum, from the Sherman Lee era to the arrival of David Franklin.

From Texas piney woods to University Circle

I grew up in Henderson, Texas, which is in northeast Texas, about 70 miles west of Shreveport, Louisiana, deep in the piney woods—rolling hills; beautiful, dense forest.

I studied liberal arts at Southwestern University [now Rhodes College] in Memphis for a year, then transferred to the University of Texas at Austin, going into the architecture program. By summer of 1967 I was beginning to see that I was not cut from the bolt of cloth that would make a good architect. I spent that summer in Europe: traveling, going to museums, and seeing great architecture. Then I did almost a year of active duty in the Air Force Reserves as a medic. By spring ’70, I had two undergrad degrees from UT—one in architecture studies and another in art history—and I wanted to see what I could do with the art history degree. You could never do this now, but I wrote a bunch of letters to museum directors saying, “Hi. I’m Tom Hinson. I’m interested in a museum career, and I’d like to talk to you.” So I started in Indianapolis, went to Kansas City, and then to Toledo where I learned the art museum was starting a new program of museum internships and applied. The last stop on my spring tour was Cleveland, about five days after the Rodin had been blown up, and I had a very interesting discussion with Ed Henning [curator of modern art 1962–85]. Luckily, I got one of the three slots in Toledo, which was a great opportunity. I learned about all phases of museum work through a professional practices seminar taught by the Toledo staff as well as by visiting with dealers, collectors, artists, and other museum professionals.

The next year I applied to a number of grad schools and got into Case Western Reserve University, which was where I really wanted to go because many of the Cleveland Museum of Art curators taught in the joint program, and I had decided I wanted to work in a museum. So I came to grad school here in fall ’71 and worked part time giving tours in the CMA’s education department. Among my various classes I was able to do directed readings on 20th-century sculpture with Ed Henning. In the fall of ’72 Ed told me he was getting an assistant and asked if I would be interested in applying. I was fortunate to be hired. My first responsibility was to manage the May Show. Ed said after I had started work, “You ought to go see Sherman” [Sherman Lee, director 1958–83]. So I went to the director’s office. Across the table, he looked over his reading glasses, which had slid slightly down his nose, and said, “Do you know what you’re getting into?”

The Transfagarasan Highway, Romania 2007. © David Leventi (American, b. 1978). Chromogenic process color print, printed 2010; 103 x 132 cm. Mr. and Mrs. James A. Saks Fund 2010.267. Courtesy Bonni Benrubi Gallery, New York

The May Show

Many people really felt that the May Show was the place to buy local art—no matter how many times the museum as an institution said, “We’re not giving our stamp of approval to these art works” because it was a juried exhibition. The downside was that the show impacted the gallery scene. Like most cities, Cleveland suffered because people interested in national or international contemporary artists tended to go to New York to do their purchasing. What that left [for local galleries] was weighted toward regional artists. By the early ’80s, some of the best artists in town were not entering the May Show, because being in another group show would do nothing for their careers. What might do something, though, was being in a carefully chosen group show. Thus came the inspiration for two Invitational exhibitions featuring a small number of regional artists, each represented by a number of works. From the beginning, Bob Bergman [director 1993–99] was concerned that the mechanism of the May Show had run its course. He wanted to do something that put regional artists in context—invitational shows, solo shows, shows that mixed regional, national, and international artists—so you could see how regional artists stood up. Doing those kinds of exhibitions would allow us not only to keep our responsibility to support regional artists but also to expose the citizens of the region to the art of our time more broadly. The museum was trying to fill many different roles, and presenting the May Show annually made it difficult to carry out our educational obligation to give attention to contemporary art because then only four shows per year could be scheduled into the major temporary exhibition space. So Bob decided we were just not going to do the May Show in the same way any longer, but instead move ahead in other directions. One translation of that impetus was Urban Evidence, a show of regional, national, and international artists organized jointly by the CMA, MOCA Cleveland, and SPACES.

His most important acquisitions

Lot’s Wife, by Anselm Kiefer, the Warhol Marilyn x 100, Arthur Dove’s Pine Tree, the Jasper Johns Usuyuki. We got a really great Richard Long sculpture [Cornwall Circle], the Jennifer Bartlett, the Susan Rothenberg, the Joel Shapiro—a nice group of [then] mid-career works. The photo collection, though, meant building something from scratch, not adding to an established collection. It was a rare opportunity and exciting challenge to create a collection covering the history of fine art photography through outstanding prints representing the major movements and key photographers. The museum was greatly aided by dealers who were aware of our goal and made terrific images available to us.

Winter Trees Reflected in a Pond 1841–42. William Henry Fox Talbot (British, 1800–1877). Salted paper print from calotype negative; 19.8 x 24.8 cm. Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund 2006.4

Building a photography collection

We started with a baseline of 44 objects. There were two great foundation blocks. One was a group of 10 by Alfred Stieglitz, made in the early ’30s. Stieglitz made it known that he was willing to give museums a special price because he believed photography should be in museums, and he offered the set of 10 for $2,000. A friend of Stieglitz’s, Cary Ross, who lived in his New York building, said that he was willing to pay half, but when Milliken [William Milliken, director 1930–58] went to raise the rest of the money, he was able to raise only $20. Ross then agreed to cover the remainder. The myth is that Ross essentially gave up half of his annual income in order to make the gift to the museum. Around that same time another donor gave six prints by Outerbridge, all carbo prints. Along with that we had a complete set of Camera Work, the quarterly journal published by Alfred Stieglitz that was illustrated with photogravures, the finest way of mechanically reproducing photographs. A Cleveland family gave the museum a complete set of Edward Curtis’s The North American Indian, also photogravures, published from 1907 to 1930. Between those two bodies of work you’ve got 2,400 photogravures. That and the 44 are the nucleus.

In 1983 Evan Turner became director. His vision was to put the photo collection on a par with the other great collections in the museum. We felt it would never be a large collection, but the game plan was to build a highly selective one, concentrating on the highest quality works by the major figures. We decided that to begin with we would concentrate on the 19th- and early 20th-century material before those things disappeared. I felt that possibly the train had already left by the early ’80s, but we were able to catch onto the caboose. Evan brought the passion, and the trustees—though some of them were dubious about photography being fine art—went along with their director. And over the years, succeeding directors have continued Evan’s commitment to building an important photography collection, which now numbers over 3,000 original prints along with some 2,400 photogravures.

Today, for the first time, there are dedicated photo galleries of about 2,000 square feet in the new east wing, providing the flexibility to beautifully showcase both the permanent collection and loan shows. There’s a support group [The Friends of Photography] that acquires photographs for the collection; the museum no longer has to start from scratch in terms of creating a collection. Now there is a good base, and the CMA just has to keep raising the bar, which I’m absolutely sure my successor will do in great fashion. It is, I think, a wonderful opportunity: the current director, David Franklin, loves photography and two of the region’s most prominent photo collectors—Mark Schwartz and Fred Bidwell—are both members of the museum’s board of trustees. The stars are aligned.

Double Portrait with Hat 1930. Dora Maar (French, 1907–1997). Gelatin silver print, montage; 29.8 x 23.8 cm. Gift of David Raymond 2008.172

Hear Tom Hinson tell stories about playing poker with Sherman Lee, mediating among jurors of the May Show, Evan Turner visiting Anselm Kiefer’s studio (which was so large the artist rode a bicycle down the length of it to turn the lights on and off), flying trustees to New York to show them Andy Warhol’s Marilyn x 100, the untimely death of Bob Bergman, Katharine Reid’s great eye for art, Timothy Rub’s advice to acquire complete collections of photography, and the importance of setting the bar high and moving it higher.

Cleveland Art, July/August 2011