Indian Kalighat Paintings

- Magazine Article

- Exhibitions

A delightfully subversive poke at British colonialism

Deepak Sarma Associate Professor of South Asian Religions, Case Western Reserve University

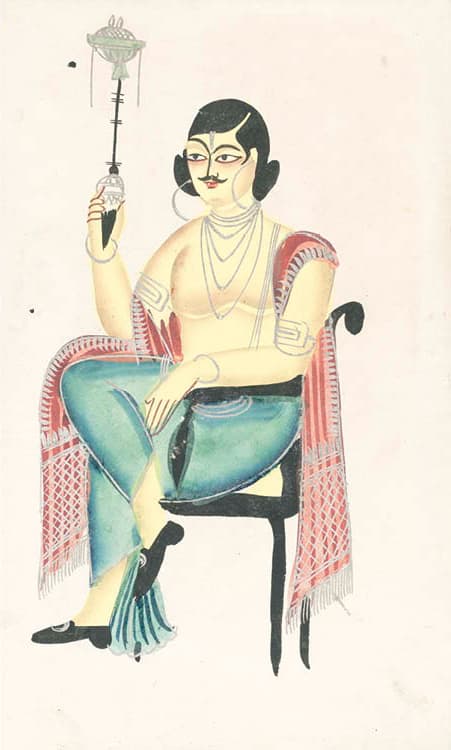

English Babu (Native Indian Clerk) Holding a Hookah 1800s. India, Calcutta. Black ink, watercolor, and tin paint, with graphite underdrawing on paper; 48 x 29.5 cm. Gift of William E. Ward in memory of his wife, Evelyn Svec Ward 2003.145

Picture 19th-century Calcutta: a dynamic and vibrant cosmopolitan city, the political capital of British India, the financial hub for trade among India, East Asia, and Europe. It was also a center for religious pilgrimage and a focal point for new movements and ideas, be they political, artistic, or cultural. The British sought to educate and indoctrinate willing colonial subjects who could then function as clerks in British East India Company offices in Calcutta. The upwardly mobile Bengalis hired by the British embraced decadence and hedonistic vices along with Western sensibilities, becoming part of a fast-changing social order.

The result was many workers who merely imitated their idealized British superiors. Known as English babus (native Indian clerks), the so-called bhadraloks (literally “well-mannered persons”) quickly became wealthy in contrast to the majority of the exploited lower-class, lower-caste Bengali service workers who did not benefit from British cultural imperialism. These babus unashamedly embraced British and European sensibilities, mores, and vices, happily surrendering to an invasive culture that could erase indigenous Indian norms. Notorious for their smoking and drinking and for keeping courtesans and dancing girls who manipulated and controlled them, the babus became ideal conspicuous consumers of the colonial world. Ironically, their British keepers, whom they often successfully emulated, did not respect the babus and certainly did not consider them to be equals.

Impoverished artisans drawn to Calcutta from the Kalighat region of rural Bengal were observers, critics, victims, and reluctant beneficiaries of the decadence made possible by their British colonial masters. From the 1830s to 1880, Kalighat painters sold their watercolor patuas (paintings) as souvenirs in bazaars in the immediate vicinity of the Kalighat Temple (a temple dedicated to Kali) in South Calcutta. A critical

response to globalization, Kalighat motifs included religious themes, Western material influence, and satirical commentary regarding the changing social order and urbanity. English Babu (Native Indian Clerk) Holding a Hookah, a caricature of a babu dapper dandy whose fashion sense combines British and Indian styles with dissonant results, is an archetypal Kalighat painting. Imitating his British superiors, he sits cross-legged on a Victorian chair, holding a hookah, sporting a Prince Albert hairstyle, and wearing buckled shoes. His posture mimics photo studio portraits fashionable among the British at the time, further underscoring the simulation. In this way, Kalighat painters ridiculed vain babus as foppish nouveau richeand offered a subaltern voice against the decadence of globalization.

The Goddess Kali 1800s. India, Calcutta. Black ink, watercolor, and tin paint on paper; 49.7 x 29.3 cm. Gift of William E. Ward in memory of his wife, Evelyn Svec Ward 2003.110.a

Sold for paltry amounts, their watercolors were simultaneously souvenirs for both Indian and British/European tourists, and inexpensive images to be used by lower- and middle-class Hindu pilgrims for worship in personal shrines. A popular image was one of the goddess Kali, a replica of the enshrined image worshiped inside the temple. Depicted with her tongue out, blood dripping from her mouth, and holding a sword and a demon’s severed head in two of her four hands, this image of Kali especially fit into the colonial imagination and Victorian popular culture—an iconic souvenir to show horrified friends back home in Britain.

Kartikeya 1800s. India, Calcutta. Black ink, watercolor, and tin paint, with graphite underdrawing on paper; 47.8 x 29.1 cm. Gift of William E. Ward in memory of his wife, Evelyn Svec Ward 2003.151

The Kalighat painters also merged Western themes with Hindu narratives in their portrayal of some Hindu gods. In the image shown here, Kartikeya—god of war and son of god Shiva and goddess Parvati, born to annihilate the demon Taraka—is depicted as a dandy. Sitting astride his vahana (vehicle), the peacock, and draped fashionably with a shawl, Kartikeya, like the ridiculed English babu, has a Prince Albert hairstyle and wears buckled European shoes—hardly the picture of a warrior. While this image certainly could have been intended for Anglophilic Indian pilgrims, or amused British, it could also have been intended for those contemptuous of British imperialism and conspicuous consumerism.

Durga Killing the Demon Mahisha 1800s. India, Calcutta. Black ink, watercolor, and tin paint on paper; 50.5 x 32 cm. Gift of William E. Ward in memory of his wife, Evelyn Svec Ward 2003.103

The Kalighat painters were delightfully insidious in their derision of colonialism and globalization. Durga Killing the Demon Mahisha may have incorporated an ingenious message of resentment and revolution. According to a myth found in the Devimahatmya (Glorification of the Great Goddess), Mahisha had defeated the gods in heaven. At their request, Vishnu, Shiva, and Brahma created the goddess Durga to defeat the demon. Barefoot Durga is depicted here on her vahana, the lion, with a sword in her right hand and her left foot pressed on Mahisha’s throat, her face ruddy with intoxication and anticipation, poised to kill him. Atypically, Mahisha is shown wearing buckled shoes. While images of Durga killing the demon Mahisha are popular and varied, no other renders him as wearing shoes. Have the Kalighat painters offered here a subtle, but powerful, insult to the British: Mahisha, a buckled-shoe-wearing symbol of the British stomped to death by barefoot Durga? Is it a portent of things to come, or a form of subversive agitation?

Kalighat images of gods and goddesses satisfied the Orientalist imaginations and preconceptions of foreign visitors who could buy proof of their “exotic” travels. They also satiated the religious pilgrims who were enamored by images of their Europeanized deities and disdainful of nouveau-riche lifestyles. In the process, the innovative Kalighat painters, transforming folk art into a popular genre, could offer scathing portrayals of the changes they observed in 19th-century colonial Bengal.

By 1900 their style changed drastically; mass production, combined with industrialization, meant that hand-drawn images were replaced by block prints, lithographs, and oleographs. The Kalighat moment was as brief and transient as the paintings themselves, whose cheaply made, low-quality papers and fugitive colors rendered them ephemeral and evanescent. The result was a brilliant and marginalized artistic movement that depicted a fleeting moment in colonial Indian history and may have been an important impetus for insurrection and, eventually, Indian independence.

Cleveland Art, July/August 2011